When Diane McCoy Lee was named “Top Teen in Public Housing” in a 1962 Chicago Housing Authority contest, she was a straight-A high school sophomore at Loretto Academy with perfect attendance. She lived in the Ida B. Wells housing project in Bronzeville with two sisters and her mother, who was paralyzed from the waist down as the result of a work injury.

She says she was obsessed with winning contests like “Top Teen.”

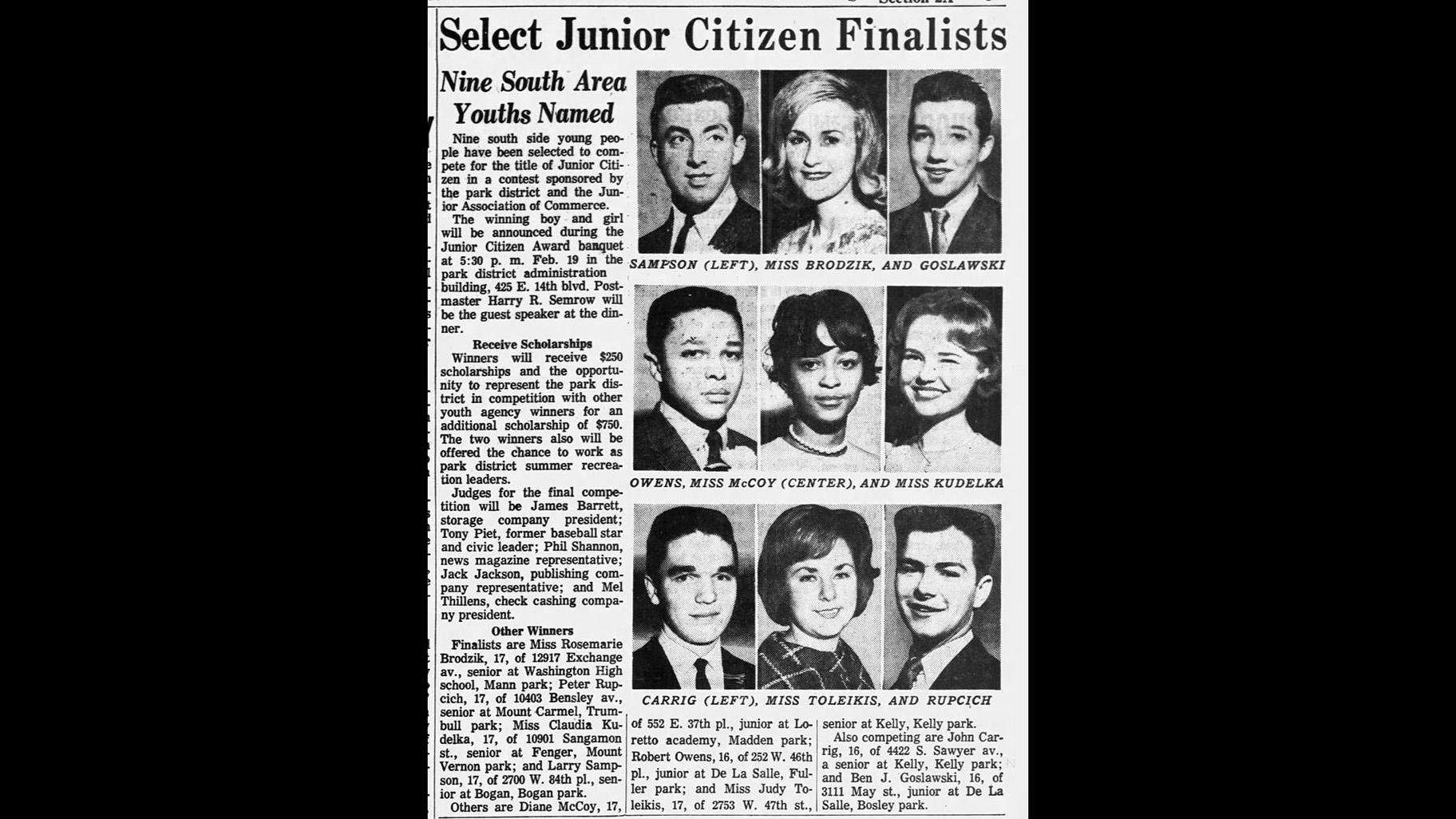

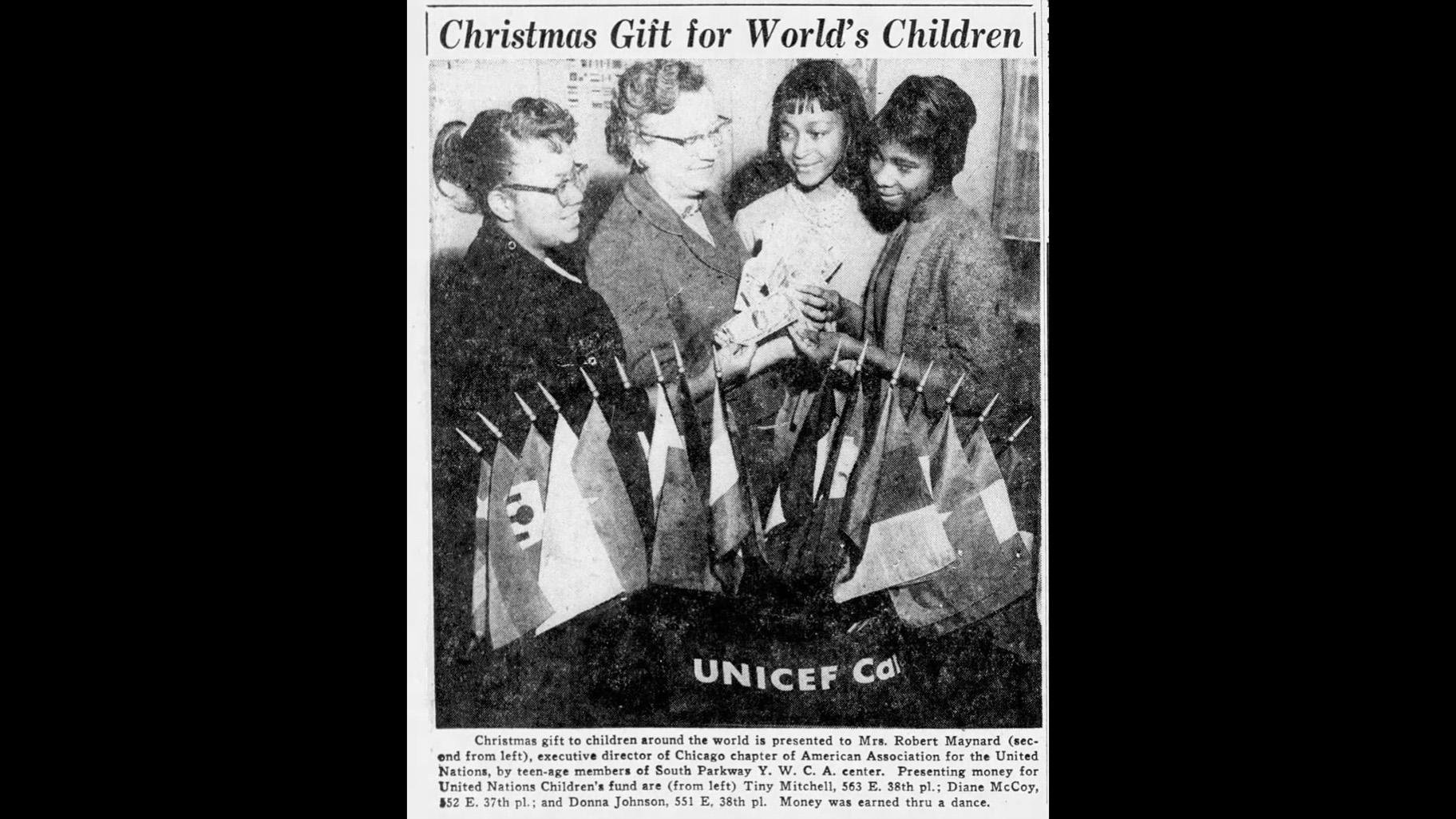

In addition to winning speech and essay competitions across Illinois as a member of Loretto’s forensics team, McCoy Lee made multiple appearances in newspapers for winning awards, and her future appeared boundless.

But just a few years later, McCoy Lee found herself a college dropout, trapped in an abusive marriage with two children. It’s an experience that, though harrowing, she says she would not change for anything.

McCoy Lee says it’s because of those dark years of her first marriage that she found her calling. While working to escape her own marriage, she blazed a trail as an advocate for other abused women in a career spanning over 40 years, in part by using the oratory skills that won her so many high school speech competitions.

“I always asked myself, why me? I was a good mother; I was a good wife. I prayed the rosary, I went to mass, I did everything that I thought I was supposed to do and I couldn’t understand why me, until I started helping other women and I realized it needed to be me,” she said.

Growing up in the Ida B. Wells housing project, McCoy Lee says the visible presence of social services in the community made her feel safe, stimulated and supported.

“On one side there was a public library that always had things for children to do. On the other side there was the park district, they had drama, tap dance and sewing, you name it. Then there was the YMCA, and they had activities. So we were surrounded by support. Everybody knew their neighbors, everyone knew everyone’s children. We had tea parties on the front steps, we had block parties. It was a good life.”

But watching her disabled mother struggle to raise three children alone after a divorce left a mark on her.

“I think watching my mother, and seeing how some of her rights tended to be denied based on the fact that she was in a wheelchair, watching her persevere, stand strong and demand that she have equal rights to those of able-bodied people, that’s probably influenced me more than anything,” McCoy Lee said. “I felt like, as I look back, I was duty-bound to validate my mother. Winning contests was my way of showing her, ‘You did a good job.’”

And though she had fond memories of her childhood, the young McCoy Lee set her sights beyond the housing project.

“It was intended to be a place for you to get started and move on beyond the housing project. I had no intentions of going to live in the project,” she said.

After graduating from Loretto Academy, McCoy Lee enrolled at Southern Illinois University to pursue a degree in social work. But once she arrived, she says the school’s size overwhelmed her, and the lack of support from home made her feel unmoored.

“I just felt lost. After two semesters I just kind of gave up,” she said. “And the boyfriend that I had prior to going was there, he was wanting to get married, and I said, ‘Oh, OK, maybe he’s going to be a good husband, he says he will.’ So we got married, and shortly after we got married I had my daughter.”

McCoy Lee’s husband was a Marine, and she says that while he was still in the service the marriage was stable. After he was discharged, however, he became physically abusive.

“It was difficult, to say the least. I tried to hang in there,” she said. “I was brought up Catholic. The Catholic Church taught you that it was the woman’s responsibility to keep the family together, and I felt that very strongly. So I did everything I could. I dealt with the abuse for years. I tried to get away a couple of times, but he always found me. He quit his job to come find me.”

McCoy Lee says she finally found help at the telephone company where she was working. She revealed her troubles to her supervisor, who brought her to the company’s health department.

“When I first went there, they told me, ‘We don’t have any help for what’s wrong with you.’ So I went back to work, went back home, suffered some more days of abuse. But something told me to go back there,” she said.

She returned to the health department, which then referred her to a homeless shelter – the only option, she learned, for abused women in 1978. Through the shelter, she was able to work with police to secure custody of her children while her husband was arrested.

In a 2006 interview with The HistoryMakers, McCoy Lee recalls a morning at the shelter when she was feeling “in the depths of despair” – but her mother’s spirit once again buoyed her:

“I was sitting outside that morning, I couldn’t sleep. I went outside, it was about five o’clock in the morning, and the newspaper was delivered. I looked in the newspaper and my mother had written an article to a columnist in the newspaper asking for me, what can I do, where can I get help and kind of described my situation. And I said, well, if my mother believes, I gotta keep going.”

Diane McCoy Lee (Facebook photo)

Diane McCoy Lee (Facebook photo)

While living at the shelter and continuing to pursue a divorce, McCoy Lee started working for the shelter, providing services to women seeking escape their own abusive marriages. As she developed as an activist, she found a new use for her high school speech skills. Once again, she traveled the state – but instead of forensics competitions, she spoke on behalf of battered women.

“I did radio shows, TV shows, I’d go places and did speeches, I did the first conference against domestic violence,” she said.

The exposure had the additional benefit of providing protection from her husband during the two-year-long divorce process. “I told my first husband, I said, ‘You better hope that I don’t fall and hurt myself because people will be coming looking for you.’”

McCoy Lee went on to become a founding member of the Chicago Abused Women’s Coalition and serve on its board of directors. By submitting the many speeches and papers she wrote about domestic violence, McCoy Lee was able to earn her undergraduate degree from Chicago State University’s University Without Walls Program in 1981.

In 1982, McCoy Lee developed and directed the first hospital-based crisis intervention program for battered women at Jackson Park Hospital. The volunteer-run effort was short-lived, running only about eight months. “It needed to be 24-hour on-call shifts – it was just too much for volunteer hospital staff to do,” she said. But it gave her a blueprint for opening the Greenhouse Shelter for abused women in Chicago, one on the North Side and one on the South Side, work she continued into the late 1990s before she and her second husband, Robert C. Lee, moved to Atlanta. There, McCoy Lee continued her work on behalf of battered women and later moved into family and child services until her retirement in 2007.

Today, McCoy Lee and her husband have retired to Oneonta, Alabama, and have eight grandchildren. But McCoy Lee remains civic-minded as ever – she is currently serving on the planning commission for the 6,600-person town.

Looking back at her decades of service, McCoy Lee says that, though the years of abuse she suffered were painful, they were also a crucible that forged her life’s purpose.

“That was what I needed to do. I didn’t think anybody could do it as well as I could, because I walked in those shoes,” she said. “I knew what the issues were because I lived it. So, no, I wouldn’t take back a minute.”