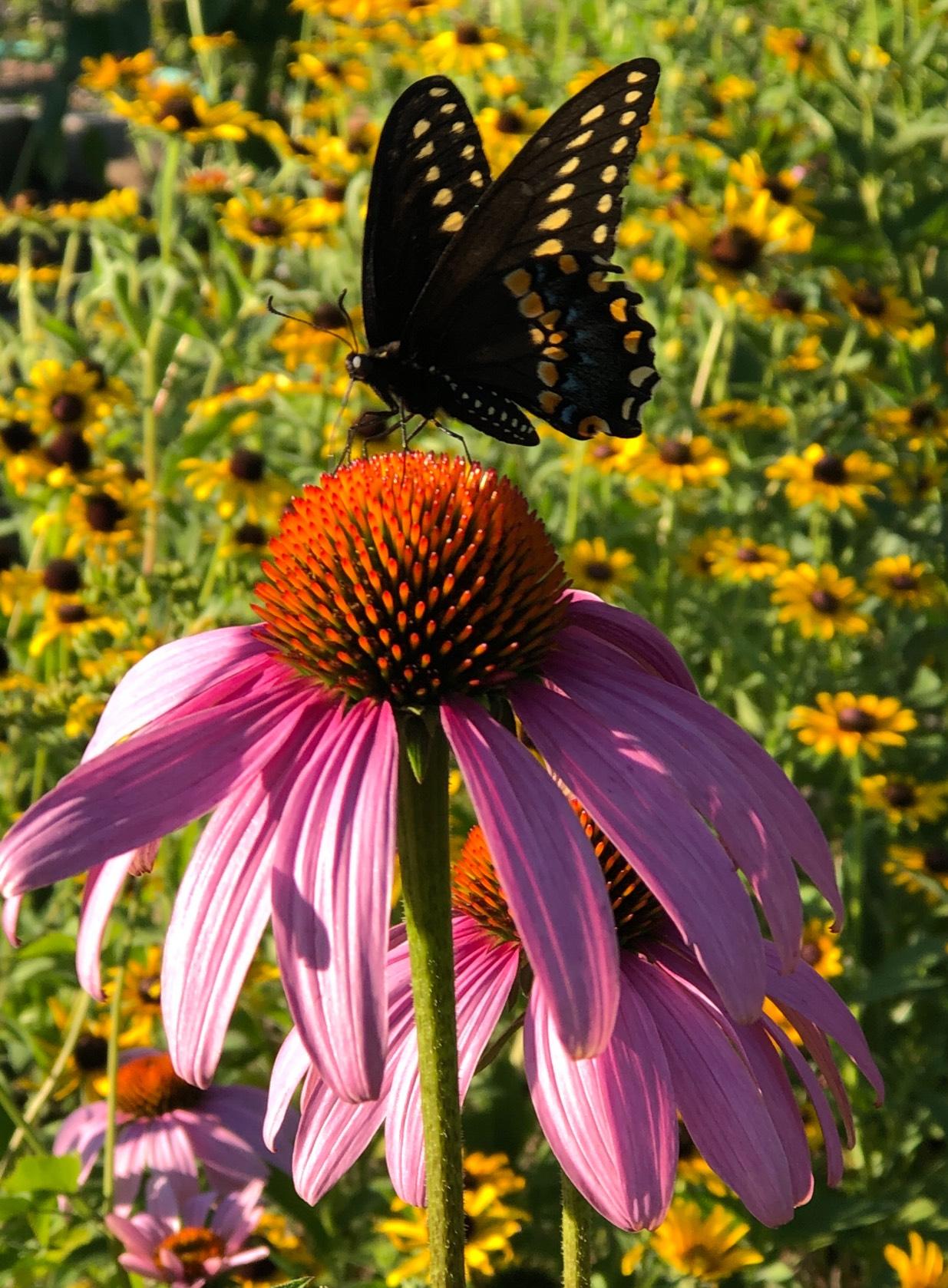

Native plants are highly beneficial for the environment, but they often get mistaken for weeds. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Native plants are highly beneficial for the environment, but they often get mistaken for weeds. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Threats of frost and snow be damned, Chicago gardeners are dreaming of visits to the local nursery, mentally planning purchases of flowers and shrubs. While many will reach for those tried-and-true friends — hostas, hydrangeas, lilacs, impatiens, geraniums, rose bushes — a growing number of gardeners are opting to incorporate native plants into their landscaping.

It wouldn’t occur to folks in the latter group to think of plants sold at a garden center as nuisance weeds, but that’s how some city inspectors view natives. And gardeners have the expensive tickets to show for it.

Now the ongoing battle to legitimize native gardens in Chicago is about to go another round.

Have you been waiting? Our plant sale is now open! You can now pre-order. We are offering plugs this year, which means a stronger plant while being easier on the wallet. https://t.co/WsPvtCRqGb pic.twitter.com/fpG6VUeZBu

— West Cook Wild Ones (@WestCookWildOne) March 16, 2021

Natives (frequently referred to as “wildflowers”) are plants that were indigenous to the area prior to European settlement. Some 1,900 species have been identified as native to the 10-county region around Chicago, and roughly 2,700 are native to Illinois, according to Greg Spyreas, a botanist with the Illinois Natural History Survey.

“They’re our natural heritage,” he said.

Because they evolved with the landscape, natives are well adapted to Chicago’s soil and climate. They tend to be drought tolerant, with roots that reach deep underground, which aids with stormwater absorption. Native plants also play an important role in the broader ecosystem, supporting native bees, butterflies and other wildlife by providing food and habitat.

This isn’t new information. The benefits of natives have been promoted by various organizations, ranging from environmental groups to gardening clubs, for more than a decade and the knowledge has gradually seeped into the public’s awareness, Spyreas said. But people’s vague notion of natives’ eco-friendly properties hasn’t been matched by a familiarity with the plants themselves.

“I grew up here. You’re raised, ‘There’s grass, there’s flowers, there’s shrubs, there’s trees,’” said Carter O’Brien, the Field Museum’s sustainability officer.

Natives don’t neatly fit into those categories, often bearing little resemblance to the European imports established more than a century ago as the Midwestern garden standard. They can be spindly in nature, even spiky, and some are capable of topping 6 feet in height. Where a knowing eye recognizes gangly plants like ironweed or Joe Pye weed for the natives they are, others just see “weeds.”

That’s a problem when the person making the mistake is a Streets and Sanitation inspector, especially when the result is a gardener receiving a substantial fine for violating the city’s weed ordinance, which is suspicious of any plant more than 10 inches tall.

“These natives are not the same as an overgrown nuisance,” said Colleen Smith, deputy director of the Illinois Environmental Council. “It’s hypocrisy to say these plants are good and then send someone out to (write a) ticket.”

Streets and Sanitation did not respond to a request for comment.

Now the gardening community is fighting back with an ordinance of its own. Ald. Brian Hopkins (2nd Ward), in collaboration with IEC and entities such as the Field Museum, has proposed the establishment of a managed native garden registry, a voluntary, opt-in listing that would protect gardeners against fines.

“This case is ready for prime time,” said Hopkins. During a recent virtual town hall held to discuss the registry, he said he’s aiming to get the ordinance passed within the next three to six months.

The alderman drew a parallel between the natives vs. weeds confusion to the issue of murals vs. graffiti. “Overzealous” removal of graffiti led to the “obliteration” of a mural in his ward, Hopkins said, which prompted the creation of a mural registry to safeguard works of public art. A garden registry would do the same for native plantings, he said.

Yet even the legislation’s supporters admit the registry is a stopgap step toward revising the weed law.

“This registry is not the finish line, it’s the starting point,” said O’Brien. “It’s a lifeline to people being ticketed.”

Natives aren’t a nuisance. Just ask bees. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Natives aren’t a nuisance. Just ask bees. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

It’s been nearly 10 years since the well-publicized story of Kathy Cummings, an award-winning gardener who got slapped with a $600 fine for violating the city’s weed ordinance in 2012. The “weeds” in question were many of the same plants that, back in 2004, had earned her first place in the native landscapes category of the Mayor’s Landscape Awards Program, sponsored by the Chicago Department of Environment.

Despite the ruckus raised by Cummings and the attention her case brought to natives, Streets and Sanitation inspectors continue to issue weed tickets to native gardeners.

Naomi Davis, founder and director of the West Woodlawn-based organization Blacks in Green, was socked with a $600 weed fine in 2018 for one of her organization’s community gardens.

Blacks in Green had invested significant time and money installing prairie plantings, and uses the gardens to educate neighbors about the power and necessity of natives in terms of creating a complete ecology, Davis said.

“It was heartbreaking, it was infuriating, it was incongruous,” she said of the fine.

Adding to the insult: The garden that drew the fine was Blacks in Green’s Mamie Till-Mobley Forgiveness Garden, planted in honor of the mother of civil rights martyr Emmett Till.

“What does a community organization have to do to please the city?” Davis asked.

But in the end, she said she “buckled” and paid the fine.

Pete Czosnyka didn’t pay, he lawyered up.

In a case of what he says was political retribution, Czosnyka was fined $650 in June 2019 for violating the weed ordinance. The irony wasn’t lost on him, he said, that the plants in his yard had been obtained from the “late, great” Department of Environment (disbanded in 2011) through its much ballyhooed sustainable backyards program.

Czosnyka challenged the fine and won thanks to a bit of luck. His case was heard by a judge who had the presence of mind to consult a construction manual for the definition of a weed, which was described as “something that’s not wanted.” Czosnyka’s garden was clearly intentional, the judge determined, and the fine was thrown out.

Though Czosnyka was personally vindicated, he said his victory was tempered by what he witnessed during his time in administrative court.

He was, he said, the only person present to contest his ticket; the rest of the cases were decided in absentia.

“As fast as (cases) could be read into the record, it was ‘Fine. Fine. Fine,’” Czosnkya recalled. “Those poor people didn’t have a chance.”

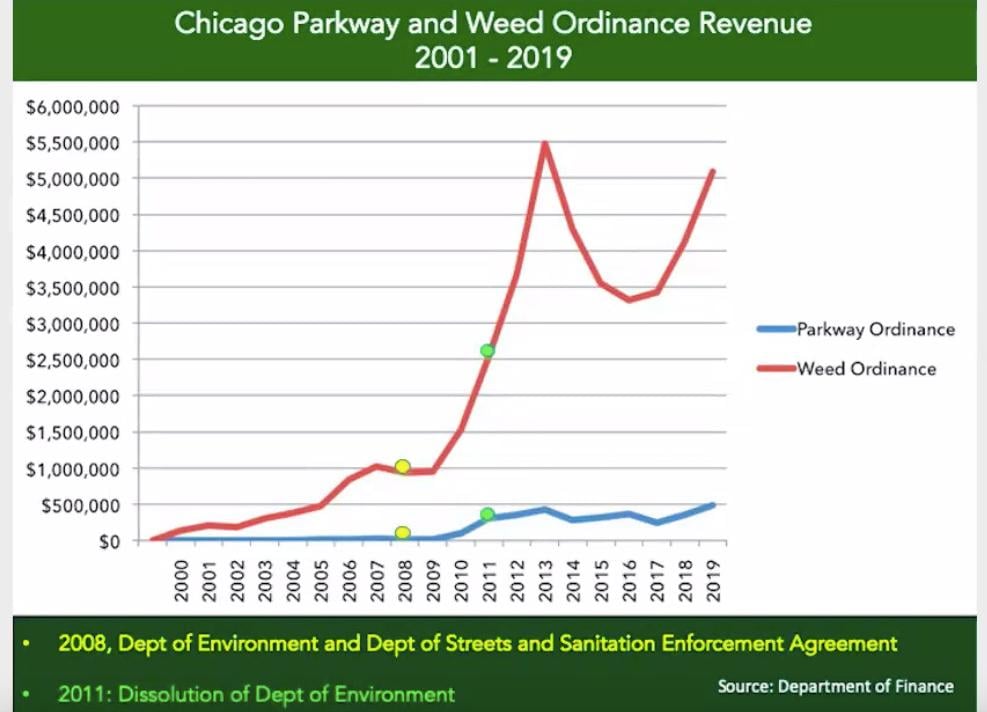

Click to enlarge. (Courtesy of Carter O’Brien / Field Museum)

Click to enlarge. (Courtesy of Carter O’Brien / Field Museum)

The Field Museum’s O’Brien spent months filing Freedom of Information Act requests with a host of city departments to obtain data on the number of citations issued for weed violations.

What he found was a brief detente between Streets and San and the Department of Environment, courtesy of a 2008 agreement that acknowledged both the city’s endorsement of natives and provided guidance on the term “weeds.” Weeds, the agreement stated, “means vegetation that is not managed or maintained.”

When then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel axed the Department of Environment in 2011, enforcement of the weed ordinance was dropped solely in the lap of Streets and San. Where the Department of Environment had supported natives, that same ethos did not trickle down to inspectors, O’Brien said.

(Inspections typically are triggered by a call to 311, a complaint lodged with an alderman’s office or a ward superintendent making observations while driving through a neighborhood.)

The number of tickets issued spiked post-2011, data shows, as did the revenue collected from fines, peaking at $5.5 million in 2013. After a brief dip following the Cummings brouhaha, violations and revenue were back up in 2019 to near record levels.

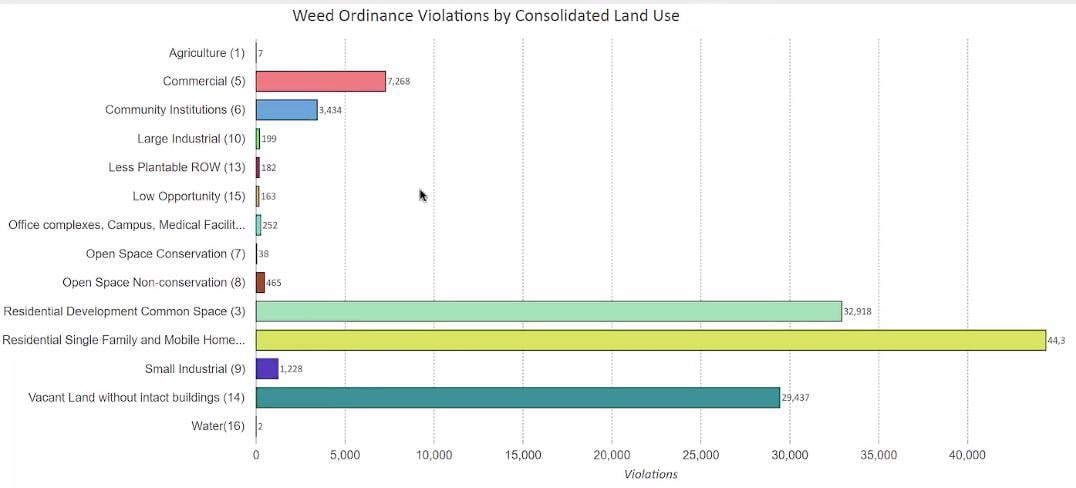

Assumptions that vacant, abandoned lots account for the majority of weed tickets isn’t borne out by the data.

Click to enlarge. (Courtesy of Carter O’Brien / Field Museum)

Click to enlarge. (Courtesy of Carter O’Brien / Field Museum)

It’s not clear how many weed ordinance violations have been levied against native gardens, but the information gathered by O’Brien shows that only 25% of the nearly 120,000 tickets issued between 2006 and 2019 were related to what’s termed “vacant land without intact buildings.” Close to two-thirds of the properties ticketed were residential, either single-family homes or multi-unit dwellings.

There’s enough awareness in the gardening community of high-profile cases like Cummings’ and Czosnyka’s to create a dampening effect around natives, Spyreas said, giving people pause about what to plant.

“The instances I’ve read about, they seem scary to people,” he said. “People are looking at their own garden and landscaping.”

While there’s consensus among gardeners that unwarranted ticketing of native gardens is a problem, there’s disagreement over whether a registry is the appropriate solution.

Prairie smoke is one of the few native plants that falls under the height limit imposed by Chicago's weed ordinance. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Prairie smoke is one of the few native plants that falls under the height limit imposed by Chicago's weed ordinance. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The Chicago Community Gardeners Association takes issue with a number of the parameters outlined in the proposed registry ordinance, including the fact that community gardens aren’t among those properties eligible for the registry, meaning some native gardens could still be subjected to ticketing.

In a list of concerns shared with WTTW News, CCGA also found fault with the proposal’s reference to “plants native to the Chicago region,” which would exclude other pollinator-friendly plants, and was particularly critical of the retention of the weed ordinance’s arbitrary 10-inch height limit.

“Referring to the City of Chicago Native Plant List published in 2011, there are only eight species that grow to a mature height of about 10 to 12 inches. Of these, the majority bloom in early spring,” CCGA said. “The height limitation prevents the cultivation of so many native species in the bulk of the garden area that the benefits would largely be lost.”

CCGA’s primary complaint, though, is one that was echoed by numerous participants in the recent town hall discussion: “The basis for the Native Garden Registry is that the city already acknowledges that tickets are erroneously being issued to home gardeners and community gardens. While acknowledging that Sanitation inspectors are issuing bad tickets, there is no effort on the part of the city to educate and train inspectors about native plants and gardens.”

It’s a fair point, proponents of the ordinance acknowledge. But after years of conversations that have resulted in very little progress, the registry is a step forward, they say, with an eye toward broader, more extensive change to come.

“I do get the larger frustration. This is something that keeps the conversation going,” said O’Brien. “The registry at least opens communication. This is the bridge that get us to the weed ordinance, it gets policymakers paying attention to it.”

THE TAMER SIDE OF WILDFLOWERS

If thousands of plants native to Chicago were already here when European settlers arrived, why is this flora only recently becoming common to area gardens?

Native plants provide food and habitat for pollinators, in a way that "classic" garden plants don't. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Blame homesickness, said Greg Spyreas, a botanist with the Illinois Natural History Survey.

Native plants provide food and habitat for pollinators, in a way that "classic" garden plants don't. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Blame homesickness, said Greg Spyreas, a botanist with the Illinois Natural History Survey.

Settlers wanted to surround themselves with the familiar, so they imported plants from their homelands, along with notions of what a garden “should” look like. And that legacy has carried forward to the present day, contributing to the sense of natives as “wildflowers” at best, or “weeds” at worst, Spyreas said.

Natives also gained a bad rap, he said, thanks to the attitude and practice of some early adopters, which boiled down to: “Let’s throw out some seed and let nature take it course.”

“There’s native plants, and there’s what’s appropriate for a garden,” said Spyreas.

Common groupings of plants like coneflowers, black-eyed Susan, phlox, bee balm and goldenrod don’t so much present a glimpse into Chicago’s prairie landscape as a curated bouquet of its greatest hits.

“We’re selecting for what we think is pretty,” he said. “In a native garden, you’re planting what you like.”

Another common misconception about native gardens is that they’re a free-for-all.

In fact, Spyreas said, native gardeners are highly meticulous and knowledgeable, with an understanding of soil conditions, sunlight, shade and bloom times. To keep plantings under control requires constant attention.

“These are people who really know their stuff. The bar is really high,” he said. “You have to really, really know what you’re doing. You’ve got to do your homework, try things out, experiment.”

The upside to all that diligence are the benefits native gardens deliver in terms of biodiversity. You can have two gardens side by side, one a traditional, immaculately manicured landscape and the other full of natives, Spyreas said, and only one, the native garden, will be abuzz with pollinators.

The other, he said, is sterile, bred for indestructibility. “Nothing eats them,” he said. “They do nothing but exist.”

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]