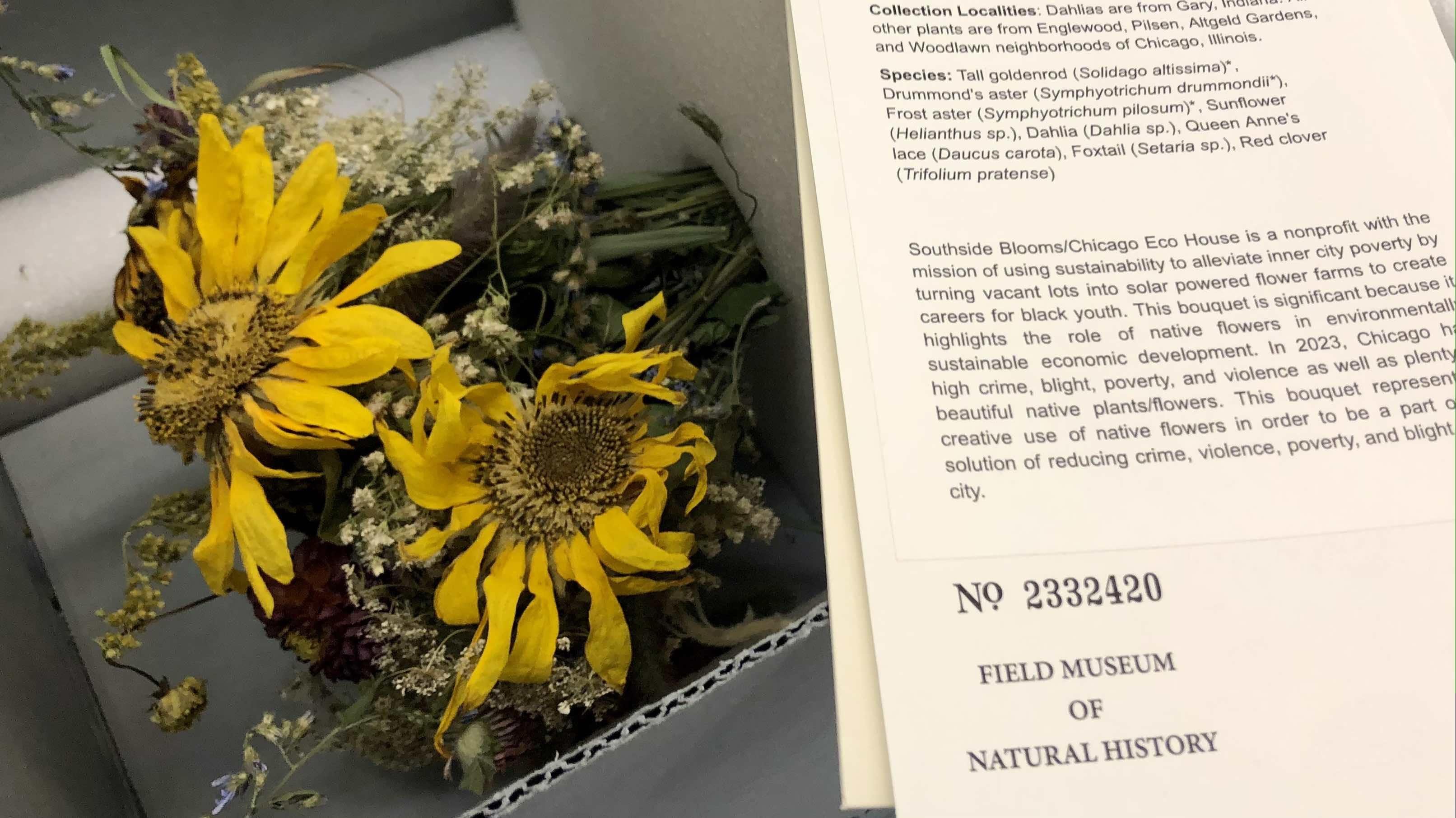

This bouquet, grown and arranged by Englewood-based Southside Blooms, is now part of the Field Museum’s permanent Economic Botany collection. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

This bouquet, grown and arranged by Englewood-based Southside Blooms, is now part of the Field Museum’s permanent Economic Botany collection. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The Field Museum’s vast holdings encompass everything from arguably the most famous T. Rex skeleton on the planet to the world’s largest collection of fossilized meteorites to millions of scientific specimens that contain the secrets of Earth’s natural history.

Among the museum’s newest acquisitions: a bouquet made up of sunflowers, asters and goldenrod stems plucked from Chicago’s South and West sides circa September 2023. The blooms are so fresh, relatively speaking, that the sunflower petals still glow a burnished yellow.

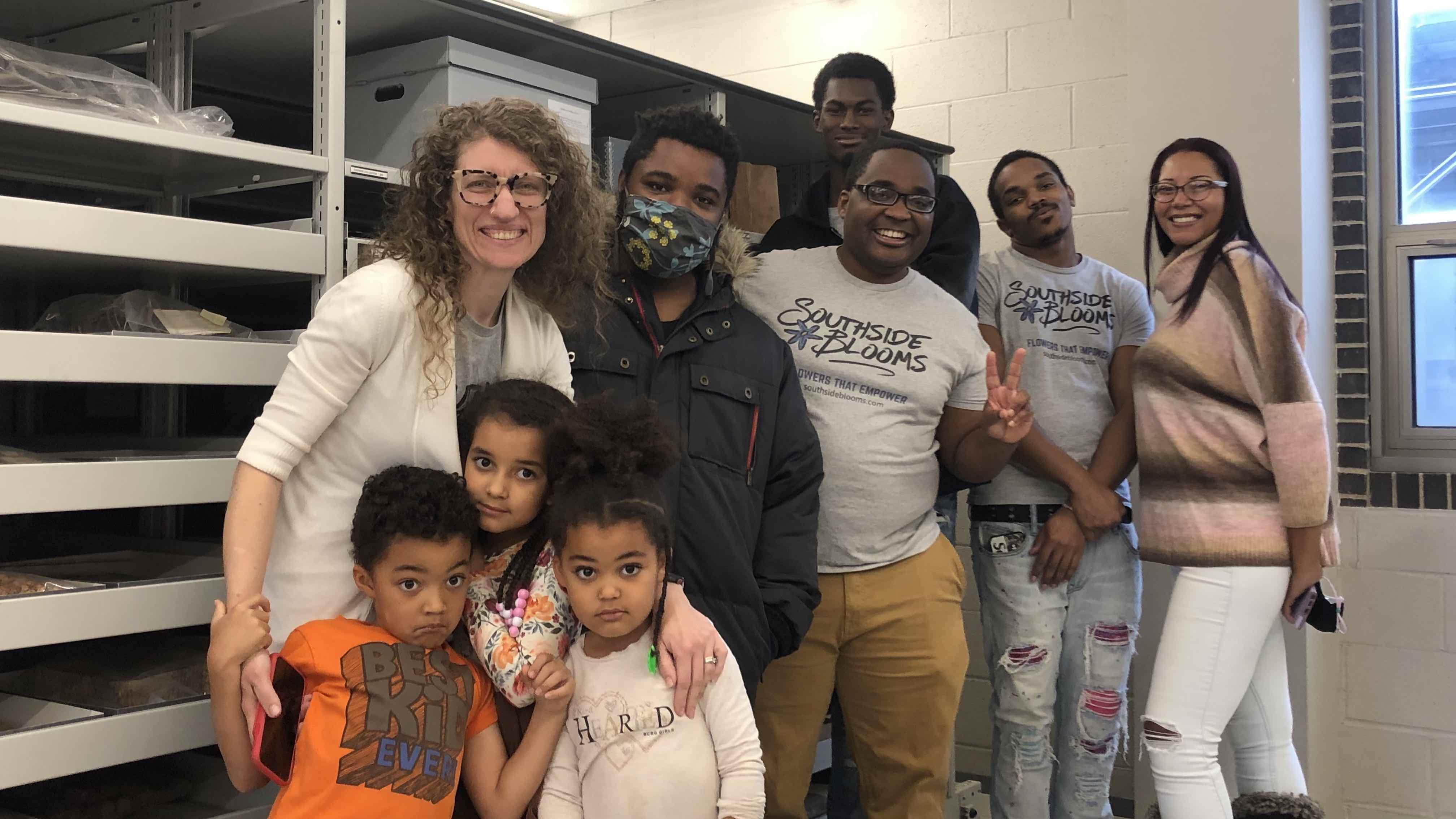

On a morning in early December, the team from Englewood-based nonprofit Southside Blooms, which grew and arranged the flowers, gathered in the Field’s herbarium for the bouquet’s official accessioning (acceptance and cataloging). No one seemed more surprised by this turn of events than Southside Blooms’ co-founders Quilen Blackwell and his wife, Hannah Bonham Blackwell.

“It feels surreal,” said Quilen Blackwell as he and Hannah Bonham Blackwell placed the bouquet, sealed in an archival box, on a shelf in the herbarium, where it’s now in the company of 500-year-old plant specimens and artifacts from the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, among 3 million other items.

“I’m still in awe. Wow — we created something that’s part of this historical record,” said Quilen Blackwell. “Our work is part of the sweep of human history. It’s very humbling.”

To understand how and why this particular bouquet earned a place at one of the country’s foremost museums — the only bouquet ever acquired by the Field, according to collections manager Kimberly Hansen — it helps to know a little something about the Field Museum’s origin story.

The museum opened in 1894 as the Field Columbian Museum, backed by a $1 million donation from Marshall Field, and its collection at the time largely consisted of items brought to Chicago from around the world for display at the 1893 Expo.

The Field’s Economic Botany collection is a remnant of that “founding” collection and is housed in the herbarium with the Field’s pressed flower/plant collection.

The latter group — some 3.5 million specimens — documents the diversity of individual plant species and is used by research scientists to study everything from how plants have evolved to the effects of climate change.

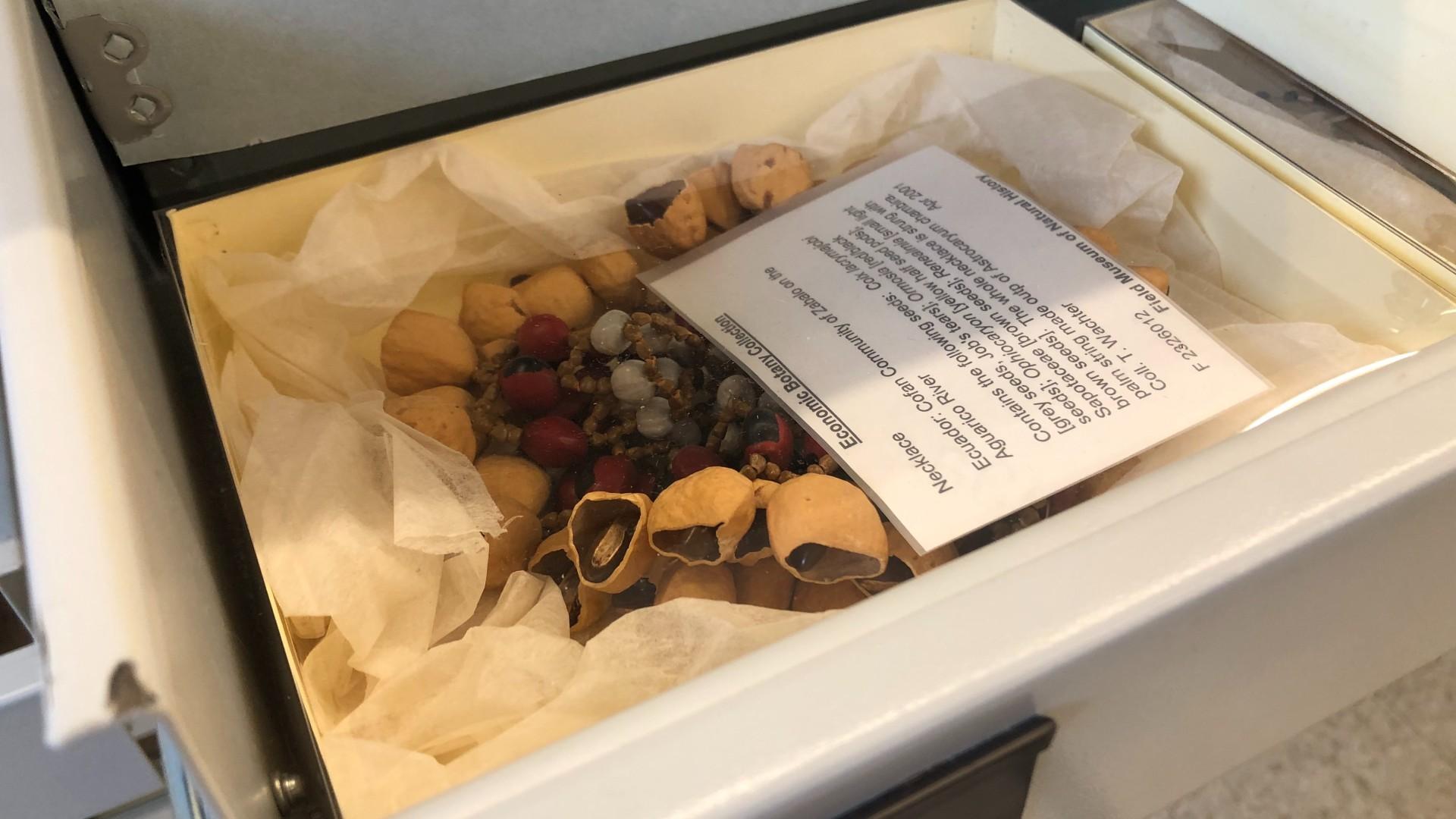

The Economic Botany collection, by contrast, consists of objects that demonstrate the role plants play in the economy. There are samples of Panama hats, hemp ropes, silk grass purses, necklaces strung with seeds, a rosary made with chestnut “beads,” wood tools and much more, including the Southside Blooms bouquet.

“It’s all plant-derived,” said Matt von Konrat, head of Botanical Collections at the Field. “This is really Marshall Field’s legacy, to make a museum of this stuff.”

In many ways, von Konrat explained, the Economic Botany collection serves as a sort of time capsule of how people have used plants in daily life, though it’s fairly rare these days to have an accessioning in Economic Botany.

“I’ve never seen so much action in this collection,” he said of the Southside Blooms celebration. “This is a very special moment.”

So what is it that future generations will learn from the Southside Blooms bouquet?

Well, that’s a multi-layered story about Chicago, and one that’s still being written.

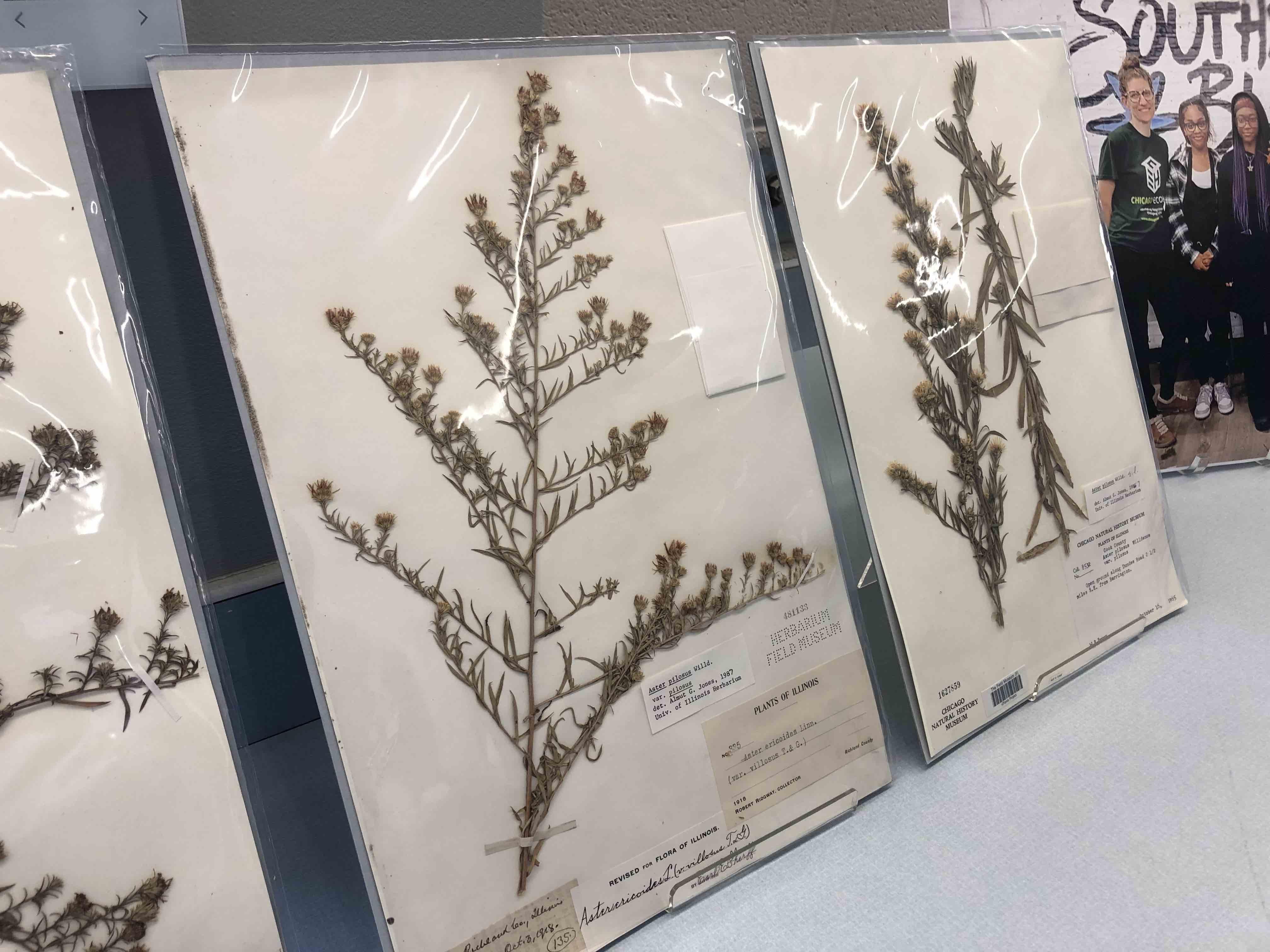

Pressed flower specimens from the Field’s collection that correspond to the ones in the Southside Blooms bouquet. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Pressed flower specimens from the Field’s collection that correspond to the ones in the Southside Blooms bouquet. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

First there’s the story told by the flowers themselves.

For the accessioning ceremony, Field staff displayed pressed flower specimens that corresponded with the ones used in the bouquet. The aster sample, according to the specimen’s notes, was collected in 1982, found growing in “weedy areas around parking lots.”

That’s how many native plants have been viewed in the past — either as weeds, or dismissed as lacking in elegance or appearance. Chicago gardeners have even famously been fined for growing natives, with ill-informed judges ruling that milkweed — the plant vital to the survival of the Monarch butterfly — is a weed, based solely on its common name.

Fast-forward to 2023, and the lowly “weedy” aster has found its way into floral bouquets.

Southside Blooms’ arrangement exemplifies this evolution, said Catherine Hu, a conservation ecologist at the Field. The bouquet documents both people’s changing perception of beauty — goldenrod can hold its own against roses — as well as Chicagoans’ increased understanding of the importance of native plants in the ecosystem, from providing food and habitat for pollinators to their deep root systems that contribute to soil health and aid in stormwater absorption.

“One hundred years from now, 250 years from now, people will be able to see what native plants meant at this time, to the point of going into bouquets for weddings, shifting the needle for what is acceptable,” said Abigail Derby Lewis, interim Chicago region program director at the Field’s Keller Science Action Center.

Homeowners, including in tony North Shore communities, are now incorporating natives into high-level landscapes, increasing their visibility. “To see them in a high-end floral arrangement gives that signal of value,” Derby Lewis said.

And in many ways, the trajectory of native plants’ acceptance parallels that of Southside Blooms, whose story is also wrapped up in the now historic bouquet.

“It feels like our work is going to change the city forever with the goals we have for what we hope flowers can do,” said Hannah Bonham Blackwell. “It feels very redemptive.”

Staff from Southside Blooms, including co-founders Hannah Bonham Blackwell (left) and Quilen Blackwell (third from left). The couple brought their three young children to the accessioning celebration. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Staff from Southside Blooms, including co-founders Hannah Bonham Blackwell (left) and Quilen Blackwell (third from left). The couple brought their three young children to the accessioning celebration. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The Blackwells founded Southside Blooms as a nonprofit in 2015. Their mission: to reverse decades of poverty, unemployment and disinvestment in communities like Englewood. How? With flowers.

Southside Blooms converts vacant lots into sustainable flower farms and employs neighborhood youth both at the farms and in its floral shop. The youth can then take that training and experience and apply it to a different field or pursue careers in urban agriculture or floristry.

“We’re unlocking something in the youth they didn’t know existed,” said Quilen Blackwell. “Flowers can be a vehicle to help their dreams come true. It’s a bottom-up economic solution.”

In the nonprofit’s early days, youth tended to cycle in and out after just a few weeks, but now many are sticking around for an average of six months, and some have been with Southside Blooms for two years.

“And they’re being promoted and given more responsibility as team leaders,” Quilen Blackwell said. “So there’s upward mobility.”

Along with giving the youth a glimpse of future possibilities, Southside Blooms is also helping them view their neighborhood through a different lens, and by extension themselves.

“Here’s this goldenrod in a vacant lot. Wait, there’s beauty, there’s nature,” said Hannah Bonham Blackwell.

“I learned to look outside the box. Now when I walk and I see different flowers, I look at the colors and take pictures and think, ‘Oh, could Miss Hannah use these?’” said Rommell Little, a Southside Blooms employee. “It sparks your creativity, to look around and see the beauty.”

The Field Museum’s Economic Botany collection consists of objects that demonstrate the role plants play in the economy, like this necklace made from seeds. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The Field Museum’s Economic Botany collection consists of objects that demonstrate the role plants play in the economy, like this necklace made from seeds. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The Blackwells’ vision of using flowers to lift communities out of poverty is a bold one, and Quilen Blackwell said “there’s definitely days where you wake up and wonder, ‘Is this thing going to happen?’”

They found a partner in the Field Museum when Amy Rosenthal, who was director of the Keller Science Center at the time, helped them plant natives at their farms to augment annuals like zinnias.

“From there (the relationship) kind of blossomed,” said Quilen Blackwell, no pun intended.

Rosenthal went to bat for Southside Blooms to become a preferred vendor at the Field and, in the same way Derby Lewis spoke of natives gaining acceptance from high-end use, that stamp of approval from the Field has in turn “unlocked a lot of opportunities” in terms of new clients, Quilen Blackwell said.

“It’s helped us to grow and expand our mission. The more business we get, the more flowers we can grow, the more people we can employ,” he said.

Beyond the economics, there are intangible victories, too.

As the accession celebration wound down, Quilen Blackwell looked around the room and saw the youth from his team peering into the herbarium’s collection shelves and chatting up von Konrat, Hu and Hansen.

“See how it brings different people together? Flowers is why you have scientists talking to kids from Englewood,” Quilen Blackwell said. “It’s bridge-building, bringing healing to our city.”

Who knew a single bouquet could have so much to say.

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]