(WTTW News)

(WTTW News)

Matthew McFarland has cycled in and out of the criminal legal system since he was old enough to do so.

“If you look at my rap sheet, it’s a 68-page horror story of somebody who was trying to deal with a horrible addiction to crack cocaine and heroin,” McFarland said.

He landed in Cook County’s Drug Treatment Court program, where he was linked to treatment services, and has now gone a little over eight years “without touching any mind- or mood-altering substance.”

“I wouldn’t be here today if it wasn’t for these medication assisted treatments and wraparound supports,” McFarland said.

He now advocates for increased access to education and resources around substance use disorder within the criminal legal system — with one area for improvement being access to medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD). These medications, like methadone, buprenorphine or naltrexone, can reduce cravings and withdrawal symptoms without producing euphoria.

The medications have been found to have a 50% reduction in mortality rate for patients in long-term treatment, meaning people are less likely to die than when untreated.

“Medication for opiate use disorder is one of the closest things we have to a miracle drug,” said Justin Berk, director of the Jail and Prison Opioid Project, a project that catalogs which facilities nationwide provide such medications.

Cook County Jail, among several other county jails in Illinois, provides MOUD to incarcerated people. Where frustration comes from advocates — and local officials — is the limitations of the Illinois Department of Corrections (IDOC) medication programming in prisons.

Currently, IDOC only provides MOUD to new patients in the state’s two women-housing prisons: Decatur and Logan correctional centers — programs that started in late 2023. IDOC said it continues MOUD for people who come into facilities already taking the medication.

When asked why MOUD was only provided to new patients at women’s facilities, IDOC spokesperson Naomi Puzzello said “the Department is working diligently to develop a plan to safely expand the MOUD pilot program to selected men’s facilities” and that “in the future, the Department plans to offer an MOUD program at all its facilities, with some as preferential sites.”

That leaves the 26 IDOC correctional facilities that house men without the ability to begin medication for new patients.

Drug- and alcohol-related mortality rates increased fivefold in prisons and threefold in jails from 2009 to 2019, according to the Pew Research Center. Nationwide, one in 13 people who were arrested and had a drug dependency received treatment while in jail or prison, according to that same study.

And in the general Cook County population, opioid overdose deaths are on pace to match a record high set in 2022. Black residents accounted for 56% of confirmed opioid overdose deaths. Approximately 80% of the cases are male.

“They need to recognize that in order for (jails and prisons) to be successful at helping to mitigate withdrawal rate and supports for long-term recovery, they have to look at medications … like methadone,” McFarland said.

IDOC said it provides the options of methadone, buprenorphine and naltrexone to about 60 individuals at Decatur and Logan. The department also provides the medication at three adult transition centers: Fox Valley, North Lawndale and Crossroads. These centers, also known as work release centers, are for individuals transitioning from living in secure custody to preparing for parole.

Meanwhile, several county jails in Illinois have been providing these services. Cook County Jail has been offering MOUD since 2014 to indivuals who were not already taking the medications.

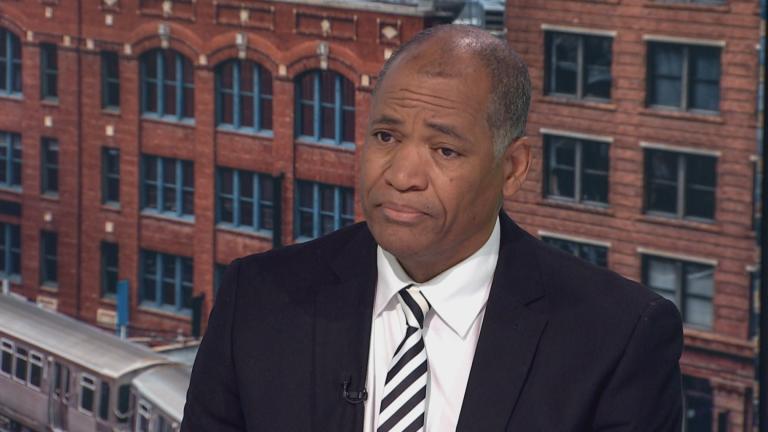

Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart said he “cannot conceive of the reason” as to why other carceral facilities haven’t gotten on board with the treatment.

“It’s a real problem and it’s wildly unnecessary,” Dart said.

He added that Cook County Jail treats individuals coming into custody no differently than people going into a substance use treatment facility.

“For a lot of the people we deal with it’s the most intensive type of approach they’ve ever had when it comes to these types of issues,” Dart said.

Dr. Priscilla Ware, who oversees Cook County Correctional Health and is medical director of Cermak Health Services, said the jail provides this care to about 700 to 1,000 patients per year. With each patient they encounter, Cermak staffers ask about opiate usage. Patients are then referred to a medical clinician who further screens them and informs them about treatment options, like MOUD.

It’s common that the first time people start MOUD is when entering Cermak’s program, Ware said.

“There are so many people out in the community who know about their friends who are in different programs, but have not been able to get into it themselves,” Ware said.

Education needs to go hand in hand with providing the medication. There’s still much stigma around accessing the medication and people might be cast aside as “drug addicts,” Ware said. In reality, opioid use disorder should be treated like any other medical issue, she added.

“Substance use disorder should be seen just as the other things that we see that require treatment,” Ware said. “It’s just like diabetes or high blood pressure that needs treatment and attention.”

Misconceptions about MOUD aren’t just from people who are trying to use it themselves. Berk, with the Jail and Prison Opioid Project, said for decades, correctional officers and wardens have viewed these medications as contraband and something they should actively try to get out of their facilities.

But treating people with opiate use disorder in carceral settings goes back decades, Berk said. Rikers Island jail in New York City has provided this treatment since the ‘80s.

Berk has seen an increase in facilities adopting policies accepting MOUD, pointing to guidance from the U.S. Department of Justice that says the Americans with Disabilities Act protects people with opioid use disorder.

That guidance writes, in part, that if “a jail does not allow incoming inmates to continue taking MOUD prescribed before their detention,” then “the jail’s blanket policy prohibiting the use of MOUD would violate the ADA.”

McFarland said care upon reentry is also vital because there’s a higher potential for overdose coming out of facilities.

“They come out with a lower tolerance to the drug because they’ve been off it for a period of time and then end up using the same amount or what they believe is a safer, smaller amount that they were on before coming in, and all too often that results in an overdose,” he said.

This care needs to be accessible for people beyond their incarceration as well, as Ware stressed “care coordination.” Cermak Health Services offers naloxone upon release. Ware also pointed to the Cook County Health Bridge Clinic, where people without regular access to doctors can be linked to different substance use treatment services.

“If we’re able to really get them while they’re here and educate them and start them on these medications, downstream we could actually have a much bigger impact,” Ware said. “You’ve actually treated their problems and they’re not going out there and redoing some of the things that they were doing because some of their medical problems had not been taken care of.”

While more facilities have started these medications, Berk said the takeaway should not be that incarceration works, but that treatment works despite incarceration.

“We should rely on medical treatment to address addiction, not criminalization — not carceral systems to be responding to this medical epidemic,” Berk said.

Note: This story was updated to clarify when Cook County Jail began offering MOUD treatment to individuals not already taking it and to reflect the number of IDOC correctional facilities for men.