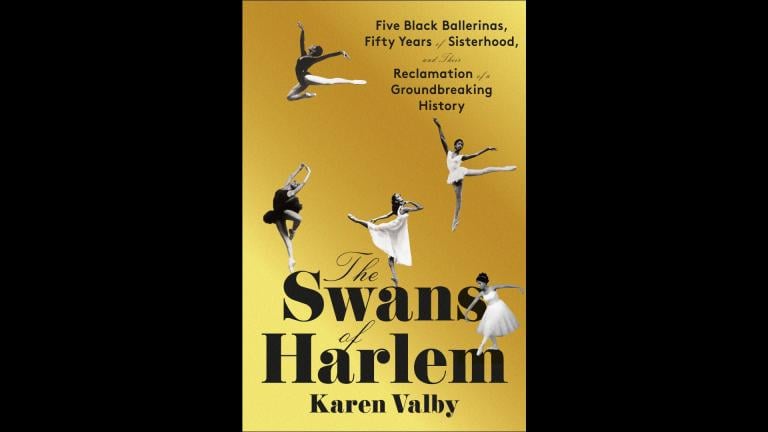

A photo of Frankie Knuckles is on display at an event commemorating the digitization of his vinyl record collection. (Angel Idowu / WTTW News)

A photo of Frankie Knuckles is on display at an event commemorating the digitization of his vinyl record collection. (Angel Idowu / WTTW News)

After eight years, the digitization of Frankie Knuckles’ vinyl collection has been completed.

The celebration of this pivotal moment comes at the 10-year anniversary of the house DJ’s passing. Known as a DJ, record producer and remixer, Knuckles is also considered the inventor or “godfather” of house music, more formally known as Chicago house music around the world. The term house came from the Warehouse, a club where Knuckles was a resident DJ. He would take existing songs and mix and remix them with other beats to create dance versions of music.

Knuckles previously shared his thoughts on the trajectory of his career in an interview with WTTW News.

“(The Warehouse) was described as church on many occasions,” Knuckles said. “It was a very spiritual experience, but it wasn’t a religious experience. It was more of a spiritual one. … People, throughout the course of the night, from the music I was playing, people would run a whole gamut of emotions, you know from being very happy to very sad and crying. Everything.”

Members of Theaster Gates’ Rebuild Foundation have been working to restore nearly 5,000 of Knuckles’ vinyl records for the last eight years.

The celebration was formally commemorated with the digitization of one final record, a Frankie Knuckles remix of Chaka Khan’s “I’m Every Woman” by Whitney Houston.

“The record was so hot, they were said to have played it five times back to back,” said Mario Gage, a cultural historian who worked with Rebuild to help digitize the collection. “Theaster introduced everything and summarized the project. Then Freddi (of the Frankie Knuckles Foundation) dropped the needle on both sides of the record. … He’s why the collection was even able to come here. Then I was behind the computer, recording the song on Audacity. So it was very symbolic to have as a full-circle moment and culmination of the time spent digitizing his collection.”

Fredrick Dunson, founder, president and executive director of the Frankie Knuckles Foundation, said Knuckles’ work in the creation and expansion of house music is still highly influential to a new generation.

“Frankie was not just a maestro on the dance floor; he was a guiding force, infusing his artistry with purpose and connection,” Dunson said. “Today, we honor his lasting influence and express our deepest respect for the unforgettable mark he left on Chicago and the world.”

Gage joined the digitization team last May. As part of one of the final teams in the digitization process, Gage said it was fun to take the project across the finish line.

“The first component was cataloging everything,” Gage said. “We spent a few months cataloging all the records. That entailed going through each record physically and assigning it with an inventory number if you will. There are just under 5,000 records in the collection. We captured the artist, the release title, all the track listing on it, from the mixes to the year, the label, all that. Then we scanned. This is comprised of scanning the sleeve, the front and back cover, the actual record itself, both sides. If it had a printed inner sleeve, we scanned that, too. Sometimes records have inserts, that too. We scanned everything associated with the object. The third part was the actual digitization. So we would sit down in real time and digitize it. ... We’d have Audacity running and would play the record in real time.”

The collection was comprised of full albums and singles created by Knuckles, as well as remixes he received from other artists through the years. Knuckles was always on the move; it’s important to note that there were many records he would have to leave behind throughout his travels. The collection also includes acetate discs comprised of music that wasn’t accessible to the public.

“They’re, like, … what’s used in the step before a test pressing,” Gage said. “It comes straight from the studio. You press it up on the acetate. It’s like a mockup if you will. It’s called an acetate because that’s the material and it’s meant to be an example to hear how it’d sound if you actually pressed it up. So the acetate is what the test pressings and commercial copies were based off of. It feels like a plate but looks like a record.”

“Frankie had a good amount of acetates in his collection,” Gage continued. “He did his own remixes of songs that were commercially released, and he also did stuff that he was playing around with. He was sometimes even given acetates of releases of something else coming out. ... So it was cool to hear stuff he had early access to, as well as music that might not ever have even made it to the final pressing. It was very cool to bring that to light, that alongside with just hearing the music he used to create a new genre that was birthed here in Chicago.”

When asked why he felt digitizing this collection was important, Gage said it’s about preservation.

“If you don’t preserve what’s already happened, it can get lost,” Gage said. “This is a way of putting Chicago and the Black and Brown communities’ official seal on the history of house music and Knuckles’ role in the history of house music. These are the blocks house music was built on — his contribution to not only music history but to Black history and to Chicago history.”

Follow Angel Idowu on Twitter: @angelidowu3

Angel Idowu is the JCS Fund of the DuPage Foundation Arts Correspondent.