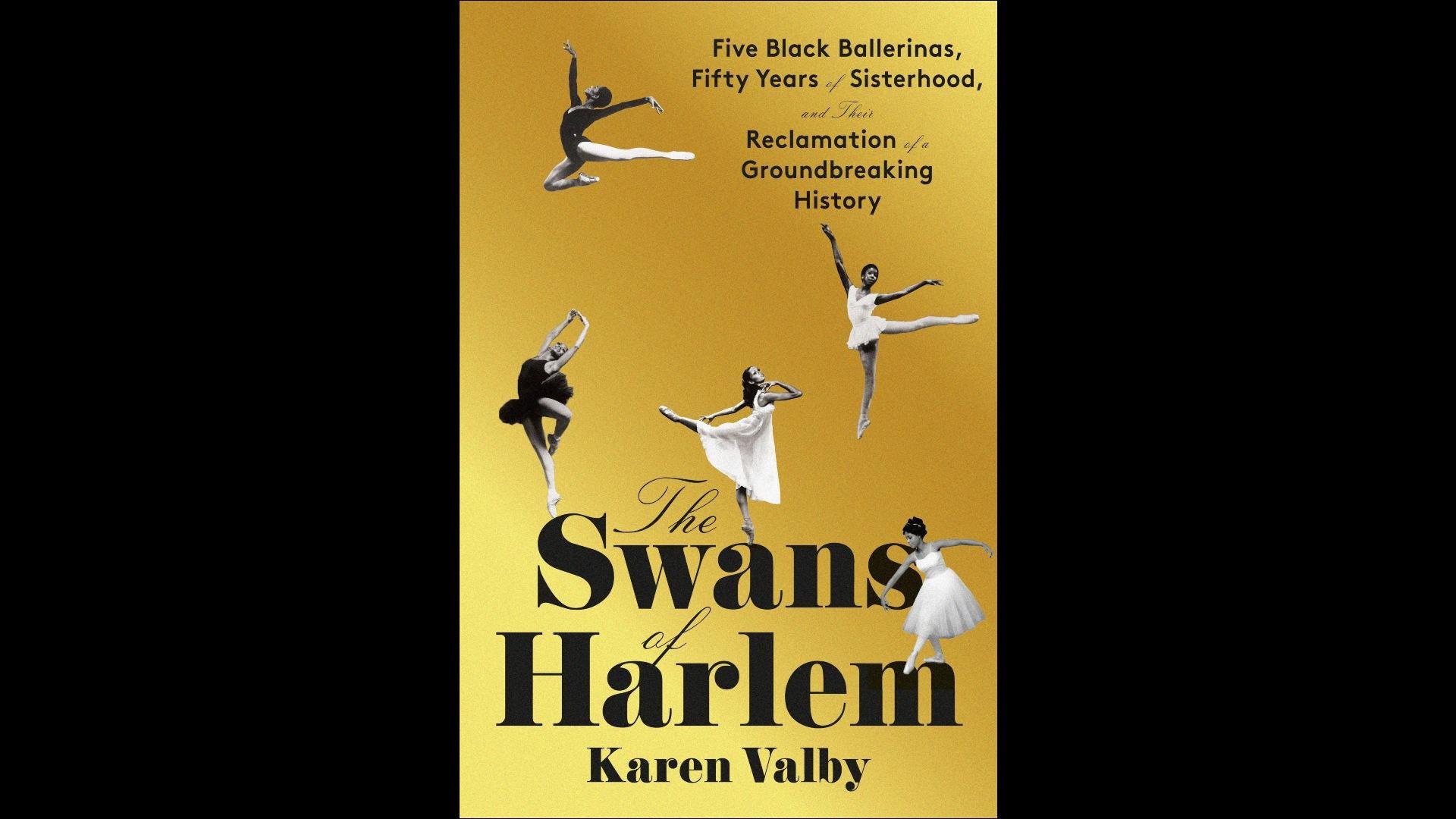

“The Swans of Harlem: Five Black Ballerinas, Fifty Years of Sisterhood, and Their Reclamation of a Groundbreaking History” (Credit: Penguin Random House)

“The Swans of Harlem: Five Black Ballerinas, Fifty Years of Sisterhood, and Their Reclamation of a Groundbreaking History” (Credit: Penguin Random House)

What started as a New York Times article published in the summer of 2021, has since turned into a book capturing the narratives of five pioneering Black ballerinas.

Titled “The Swans of Harlem: Five Black Ballerinas, Fifty Years of Sisterhood, and Their Reclamation of a Groundbreaking History,” the book tells the stories of a group of Black ballerinas at the Dance Theatre of Harlem. Featured are founding members Lydia Abarca Mitchell, Gayle McKinney-Griffith, Sheila Rohan and first-generation dancers Karlya Shelton-Benjamin and Marcia Sells.

The dancers will appear as part of a Chicago Humanities Festival event on Saturday, April 27, at Francis W. Parker School, 330 W. Webster Ave., where they will share their own stories and speak to the enduring bond they share.

Together they made history under the direction of Arthur Mitchell, co-founder of the Dance Theatre of Harlem, and the first Black principal ballet dancer with the New York City Ballet.

As the adoptive mother of two Black girls with a passion for performance, Karen Valby, the book’s author, found herself connecting with the Swans of Harlem.

“To me one of the main purposes of this book was to let my daughters know, or other Black girls who are the only one in their dance studio or classroom, that there is a long list of examples that awaits you,” Valby said. “... If we don’t tell their stories, we erase them. If we deny their existence, then my daughters are robbed of examples and are left to feel more isolated and alone.”

Valby said there is one line that often comes up from the book, “‘I was there, we were there’ and so to me this is just a celebration of existence.”

Abarca Mitchell said Valby understood the sense of frustration that was shared by the dancers about their legacy.

“Having done all that work 55 years ago and no one knows about it,” Abarca Mitchell said. “We wanted our stories to come out of our own mouths. After the [New York Times] article came out, more people said they wanted to hear our stories. We had no idea it was going to turn into this, but I’m glad it did.”

Shelton-Benjamin said these stories speak to a larger effort to have Black people and their history documented.

“We are responsible for our own stories, and this has given us the opportunity to tell our own stories and place it properly in history,” Shelton-Benjamin said. “Black history, ballet history … Dance Theatre of Harlem history.”

Abarca Mitchell said she grew up in the projects in Harlem and had always wanted to dance, but initially had no interest in being a ballerina.

After receiving a scholarship to The Juilliard School, she was encouraged to receive formal ballet training. She eventually put her pointe shoes down after six years of training. That was until she got word that Arthur Mitchell was teaching ballet at Harlem School of the Arts through her sister.

“I thought, I’ve never had a Black ballet teacher,” she said. “Maybe he’ll make it more relatable and I’ll get it. I had six years of training and didn’t know what it was for, but he told me what it was for.”

That collaboration proved important.

“He’d say, ‘We’re doing something that needs to be done … we need to show we can do ballet,” Abarca Mitchell said. “We always knew we could do it, we just needed the opportunity, and that’s what he gave us.”

Shelton-Benjamin began dancing at an early age and said she was usually the only person of color in the room.

“When I auditioned for Dance Theatre of Harlem, this big whole world opened up, and there were others like me dancing ballet,” Shelton-Benjamin said. “I said this in the book that when I auditioned and went backstage to put on my pointe shoes, the ladies were backstage spraying their pointe shoes their skin color and their tights were their skin color, and for me that was it. I knew I was home.”

The larger importance of their work with the dance company was not always at the forefront of their minds.

“But Mitchell would always tell us that what we’re doing was much bigger than ourselves,” Shelton-Benjamin said. “And while you’re in it, you can’t see it. You just know you’re working hard every day taping up those shoes.”

The hard work also resulted in a deeper affection for what they brought to the stage.

“For me, I was very conscious because I was so green,” Abarca Mitchell says. “But because of [Arthur] Mitchell’s drive, we always strove to be the best … and it became our passion. You’d call it passion right Karlya?”

“Absolutely,” Shelton-Benjamin responds. “There’s nothing like it. The feeling before the curtain goes up, the smell. It’s a high. Like an adrenaline rush. It’s like you’re in a bubble and nothing can touch you.”

One of the founding members of the Dance Theatre of Harlem, Gayle McKinney-Griffith, died late last year. Valby recalled a memory that she shared that related to that passion.

“She once said something so beautiful about leaving the wings for the stage,” Valby said. “Gayle said it was like … you have all the stress in the wings, the expectations, the memories of your teacher’s criticism, your reviews … just the tedious noise of life. And then you break through this energy curtain when you get on stage. If you’re really good and really prepared, you’re able to let your art take over.”

While this book serves as physical documentation of the dancers’ role in ballet history, its author says she hopes readers take away a stronger understanding of the importance of community.

“It’s about the grounding force of sisterhood,” Valby says. “We often see the trope of Black women who are competitive and don’t have each other’s backs. These women have been friends for over half a century, and have always been in their greatest power with each other.”

“The Swans of Harlem: Five Black Ballerinas, Fifty Years of Sisterhood, and Their Reclamation of a Groundbreaking History,” is set to release April 30.

The Chicago Humanities Festival event takes place Saturday at 7:30 p.m. For more information, visit the event’s website.

Read an excerpt from the book below.

Prologue

At the height of the Civil Rights Movement, Lydia Abarca was a Black prima ballerina for a major international company, starring in iconic works like Balanchine’s “Agon” and “Swan Lake,” Jerome Robbins’ “Afternoon of a Faun,” and William Dollar’s “Le Combat.” Critics described her as “the dreaming soul of dance,” and “a living ode to beauty, incapable of an ugly gesture or a false movement.” She was the first Black ballerina ever to grace the cover of Dance magazine. She performed for queens and kings, in the movie production of The Wiz, for Bob Fosse on Broadway. She was one of Revlon’s original Charlie’s Girl models. An Essence cover star. The object of affection for everyone from Mick Jagger to David Bowie. Roses collected at her feet around the globe.

Half a century later, during Black History Month, Abarca’s thirty-two-year-old daughter Daniella wanted to brag about her mother to their friends and family. She went looking for evidence of all Abarca had done—all the barriers she had broken, all the history she had made—but in researching the history of Black ballet, she could only find stories about one young woman, Misty Copeland. Misty Copeland, Misty Copeland, Misty Copeland. The first Black ballerina, insisted the internet. And, indeed, in 2015, Copeland became the first African American woman to be promoted to principal dancer at ABT, breaking the company’s seventy-five-year record of whiteness. Thank God for Copeland’s talent and her perseverance, for the breaking of poisonous runs. But why, Daniella cried, had her own mother been so thoroughly disappeared in the telling of Copeland’s accomplishments?

Just days later, Abarca’s only grandchild, Hannah, came home from preschool in the suburbs of Atlanta, her head flooded with stories about the singularity of Misty Copeland. Four girls in her class had chosen the ubiquitous ballerina as the subject of their Famous Black Americans project. Hannah had sat confused on the class rug, listening to how Copeland had been the first to kick down doors so that children like her could live more comfortably in their dreams.

“But what about Grandma,” Hannah blurted out at the dinner table that night.

Daniella was furious, unsure where even to direct her anger. “Where’s your name?” she cried to her forgotten mother. “Where’s your name?”

George Balanchine, long considered the father of American Ballet, and the co-founder and artistic director of New York City Ballet, was famously said to prefer his ballerinas “the color of a peeled apple.” (His apologists insist he was only talking about Suzanne Farrell, one of his most iconic muses.) To this day, City Ballet has yet to anoint a Black principal ballerina.

But it was also Balanchine, along with his City Ballet co-founder Lincoln Kirstein, who recognized greatness in Harlem’s own Arthur Mitchell and encouraged his rise to become the company’s first Black principal dancer. Kirstein had been in the audience for Mitchell’s graduation exercise at the School of the Performing Arts, when he performed a solo entitled “Wail,” choreographed to Bela Bartok’s music. Mitchell had lacked formal dance training when he’d been accepted into the school, relying instead on his exuberant sense of showmanship, auditioning in a rented white top hat and tails with a tap dance routine to Fred Astaire’s “Steppin’ Out with My Baby,” taught to him by a vaudevillian performer he’d looked up in the phone book. Throughout his time there, he withstood pressure from the school’s administration, pushing him towards modern dance. “It was better for ‘primitive peoples,’” he explained to a People reporter in 1975. “I said to hell with that; I wasn’t raised speaking Swahili or doing native dances. Why not classical ballet?”

Upon Mitchell’s graduation, Kirstein offered him a scholarship to the School of American Ballet, the preparatory school for the New York City Ballet, telling the young dancer what so many successful Black people know to be true: “Lincoln put it to me with brutal frankness,” Mitchell said. “He told me I would have to work twice as hard as anyone in my class.”

Mitchell entered the company in 1955, the same year a weary Rosa Parks was told to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama, bus. Some critics reduced a Black man in City Ballet to a “casting novelty” on Balanchine’s part. Some said worse. In his debut performance, Mitchell appeared on stage with Balanchine’s then-wife Tanaquil Le Clercq in “Western Symphony.” At the sight of him, an old white man seated behind the conductor exclaimed, “My god, they’ve got a n***** in the company!” Commercial television would hold out for years before it aired a performance of Mitchell partnering a white woman, but in 1968, he and Suzanne Farrell danced a pas de deux from Balanchine’s “Slaughter on Tenth Avenue” on The Johnny Carson Show. “And in living color, darling!” he cheekily told a reporter afterwards.

Balanchine helped launch Mitchell into stardom by setting his 1957 abstract masterpiece, the central pas de deux in “Agon,” on his lone Black danseur and the white Southern ballerina Diana Adams. “My skin color against hers, it became part of the choreography,” said Mitchell. His athleticism and technique were put to the highest test in a dance that was as sensual as it was intricate and austere. When a stagehand in the South balked at training the spotlight on a Black man, Balanchine told Mitchell to call upon the reserves of his own internal glow. Fellow City Ballet principal danseur Jacques d’Amboise remembered before his death: “[Mr. Balanchine] said, ‘You know, just make light brighter and don’t worry.’”

Mitchell turned the lights up in every room he ever entered. On stage and off, the force of his beauty and charisma hit like a wave. The man had key hooks for cheekbones and flashbulbs for teeth. He didn’t smile; he shone. He didn’t just dance; he set a stage aflame. His herculean work ethic and his preternatural gifts as a performer, coupled with Balanchine’s favor, earned him groundbreaking agency over his destiny. He became the first classical Black premier danseur in history, a beloved international star who performed on classical stages around the world, on Broadway, in the movies. Everywhere he went, critics hailed him as the exception to the rule that Black people had no place in ballet. But where some might rest, fat on individual achievement, Mitchell only looked outside of himself, wanting to do more.

In 1968, his career at City Ballet still going strong, Mitchell was under commission to form the National Ballet Company of Brazil in Rio de Janeiro when news of Dr Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination shook him awake, the national trauma igniting within him a sense of spiritual purpose. He knew then that he was needed at home. He decided to build a ballet school in Harlem, the neighborhood that had raised him up. And because children deserve role models who show them what is possible, he would simultaneously establish the first permanent Black professional ballet company.

Art is activism. Let the gorgeous lines of his dancers’ bodies serve as fists in the air.

When the school started, in a church basement that doubled as a basketball gym, Lydia Abarca was a teenager living in the projects in Harlem with her parents and six younger siblings. She’d never had a Black dance teacher before. She’d only performed once in her life, as a fourth grader at St. Joseph’s Catholic School, to a nun’s choreography of “Waltz of the Flowers” from The Nutcracker. But as soon as she descended those basement stairs, Mitchell grabbed hold of her long, elegant feet and swept her into his tornado.

Abarca was a girl who loved to dance, who wanted to be a star, who fantasized about making enough money to buy her devoted parents a house, to move them out of the projects. She wanted to be like her childhood heroes Ginger Rogers and Natalie Wood, emerging from limousines onto red carpets to snapping bulbs, the plot of her life playing out like one of the feel-good “Million Dollar Movies” she loved to watch on her family’s black-and-white television. And for a flash of time, a decade of her youth, she had a taste of all that, as Mitchell’s muse and Dance Theatre of Harlem’s first prima ballerina.

But by the time her granddaughter came home asking about that history, all that was left were a few dusty plastic bins in the basement full of yellowing photographs, stacks of old programs, and an invitation for Abarca to perform for the Queen Majesty. There were old profiles from People and The Washington Post that delighted in the star power of Mitchell’s young ballerina. Her face beamed from magazine covers, reviews marveled over her beauty and talent, her exquisite profile and flower stem neck had been etched into a Revlon perfume box. Whatever remained of her spotlight years now lived in a couple of click-top bins and a shaky eleven-minute VHS recording of her breathtaking pas de deux in Balanchine’s “Bugaku.”

Daniella knew the bones of her mother’s past. But what she experienced in the day-to-day was a modest woman who took her administrative work in a doctor’s office seriously, who’d taught ballet classes in Daniella’s elementary school cafeteria, and later helped her high school step team on their routines. She knew that her mother kept her figure to a strict size eight and that she booked extra work on local movie productions to make some cash on the side. And she also knew that in the evenings her mother drank too much rum, to the point that Daniella kept Hannah away from her, to spare her child from seeing her beloved grandmother slur or stumble. She’d found the empty bottles hidden in her mother’s trunk, behind her hair products under the bathroom sink. Daniella, a pastor and single mother, understood that Abarca was lost or unhappy in ways she didn’t yet have the language to express.

The gaslighting of one’s own history will mess with a person’s head. Abarca was losing grip of herself. The past and present had to converge if she was going to find any real way forward. She’d need the women who were with her at the beginning of it all alongside her again. And they, it turned out, needed her too.

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, divorced from the normal rhythms and routines of their lives, five founding and first-generation Dance Theatre of Harlem ballerinas formed the 152nd Street Black Ballet Legacy Council, named for the street they helped make famous. Lydia Abarca-Mitchell (no relation to Arthur), Gayle McKinney-Griffith, Sheila Rohan, Marcia Sells, and Karlya Shelton-Benjamin had held each other up half a century earlier and they would do so again through the terrifying trudge of Covid. They all had been knocked off balance by the anointing of Misty Copeland, by what felt like the deliberate scrubbing of their groundbreaking history. They would make peace with quarantine by gathering online every Tuesday afternoon, to throw out an anchor to one other from their scattered perches across the country. They would take advantage of the time to try and right a grievous wrong—they would take control of their own history. However daunting that task may have seemed, no matter. They had accomplished the impossible before.

These five intrepid girls had come together and made one of the most iconic childhood fantasies come true. Originally strangers, in so many ways, they couldn’t have been more different from one another. Contrary to early in-house fundraising press releases that described Dance Theatre of Harlem’s dancers as “black slum youngsters” and “high school drop-outs,” they were each unique human beings who came from specifically loving homes. Lydia Abarca was raised by working-class parents and had been bound for Fordham University on a partial academic scholarship when she first met Arthur Mitchell. Gayle McKinney-Griffith’s father was a draftsman at a submarine engineer firm, and she was raised in a two-story colonial house on acres of land in Connecticut. Sheila Rohan’s father died when she was a baby and her immigrant West Indian mother cleaned houses in Staten Island to put food on the table for her eight daughters. Marcia Sells grew up on a Cincinnati cul-de-sac with a father who had his PhD and a mother who went back to school for her Master’s in her forties. And Karlya Shelton grew up in Denver in a working-class family that belonged to the local AME church and took elaborately planned road trips every summer to national landmarks in their Chevrolet station wagon.

What they shared was a calling to the classical stage.

It’s a rite of passage for so many children, to spend some portion of Saturday dressed in leotard and bunching tights, standing in buckling row of other knock-kneed ducks. A childhood spent twirling in front of a mirror. The future is like a snow globe, where a young girl imagines herself as the star, fairy dust floating down upon her graceful limbs. There is perhaps no more traditional, and traditionally white, feminine ideal than the ballerina—immune to gravity, the embodiment of an aesthetic too pure and fabulous for the grounding of our tedious world. Now imagine a little Black girl twirling in front of her bedroom mirror in a country that has yet to pass the Civil Rights Act or the Voting Rights Act. The innocence and audacity of that child’s dream.

Karlya Shelton was seventeen years old when she became the first Black American chosen to represent the United States at the prestigious international Prix de Lausanne competition in Switzerland. “The thing is, I never thought of ballet as a white artform,” she says, “because I could do it. So how could it not belong to me too?” These women missed out on meandering childhoods of slumber parties and pep rallies and school dances. They trained in pointe shoes that felt like cement blocks on their feet, practicing until their toes bled. They obsessed over their every line and angle and gesture. And they gave of themselves gratefully. All that discipline, all that grind, undertaken as acts of love. They worked to master their technique so they might experience the ecstasy of breaking free of their self-conscious mind on stage. They quested for perfection while living with the knowledge that a ballerina will dance a flawless performance just a handful of times in her entire career. Says Shelton: “When you get it right, when everything works, there is magic. You become the music and you let it carry you and you ride on it like waves.”

McKinney-Griffith describes ballet as her “choice of expression.” Before every performance she’d knock three times on the wooden stage for luck, then cross over from the mortal to the divine. “It’s like there’s an energy curtain,” she says of that last steadying breath in the wings, exhaling out the calamity of expectation. “And then you break through it. You almost feel birds flying over your head on stage. It’s so powerful because that’s when you break free of your stress. No more training. No more pressure. You show your gift.”

“Yes, that’s exactly it, Gayle!” says Shelton. “This was our gift. This is what we were given. To deny ourselves, or anyone else, of our gift? No, that just wouldn’t do. We danced because we loved to dance, and we loved dancing with each other. We felt beautiful on stage together. There was a love between us that was tangible.”

Now, years later, when the Legacy Council is able to gather in person, their bodies curve together in a circle. As they speak, they reach for one another’s hands or lean to touch shoulders, their proximity bolstering, providing cushion.

“These are my sisters,” McKinney-Griffith says. “We first came together at a very special time in our lives. Then we’d all gone off and had our own journeys. And now here we are coming together again in our old age. We’re still a nucleus. We’re able to tell each other all that we’ve been through. We laugh, and laughter is healing. And we can cry too, because we’ve taken all our burdens and thrown them out.”

“These were women of great courage,” says Tania León, Pulitzer Prize-winning composer and Dance Theatre of Harlem’s first musical director. “There was something in them that believed in themselves, and nothing was going to stop them. That is something Arthur had a good eye for—that commitment. I remember when Sheila Rohan danced ‘Concerto Barocco’ the first time. She was literally crying because her feet were in so much pain.”

At eighty-one-years old, a great-grandmother seven times over, Rohan is the oldest of the five women. She was a twenty-eight-year-old mother of three when she first joined the company, keeping quiet about her age and about her children back home so as not to jeopardize her acceptance. “You know how they talk about planting seeds?” she says. “Arthur Mitchell planted a seed in me, and these women helped to nurture that seed and make it grow. It was like a rebirth for me. I felt strong. I felt confident. I started to know myself. Coming from Staten Island, I was a country girl from the projects. My first time on a plane was to go to Europe to dance on stages in theaters that looked like museums. I thanked God every day for the experience. But you put things behind you. You move on. Coming together again, I remember how much it all meant to me. I didn’t have to be a star ballerina. It was enough that I was there. I was there. I was there.”

I was there. I was there. I was there.

Reprinted by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Excerpted from The Swans of Harlem: Five Black Ballerinas, Fifty Years of Sisterhood, and Their Reclamation of a Groundbreaking History by Karen Valby. Copyright 2024 Karen Valby. All rights reserved.

Follow Angel Idowu on Twitter: @angelidowu3

Angel Idowu is the JCS Fund of the DuPage Foundation Arts Correspondent.