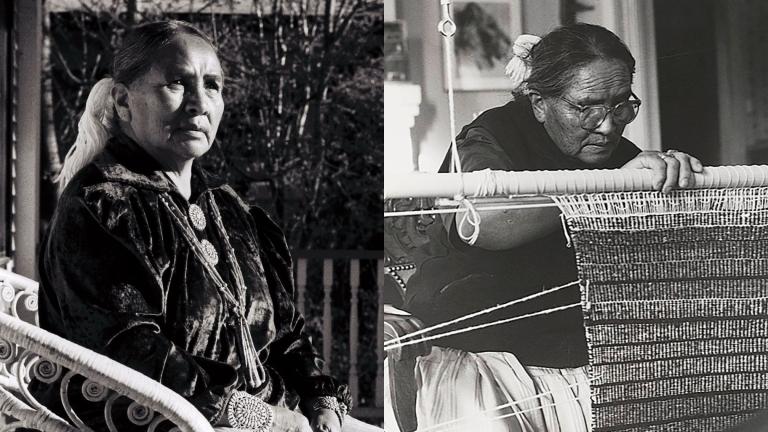

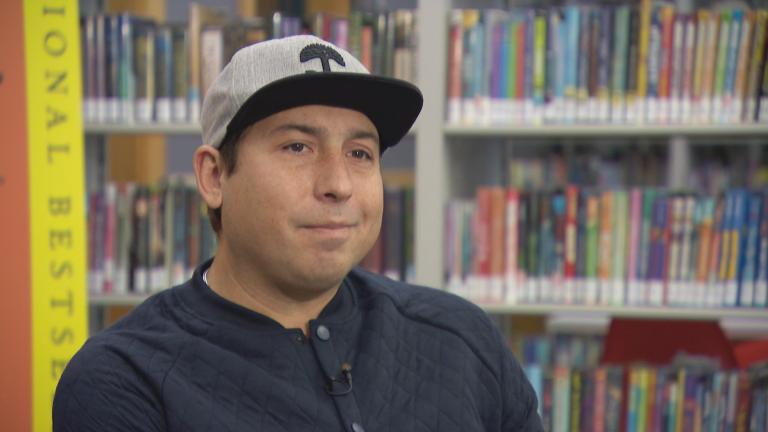

Joseph “Zeke” Rupnick, tribal chairman of the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation, speaks at a news conference at the Illinois Capitol in February 2024. (Peter Hancock / Capitol News Illinois)

Joseph “Zeke” Rupnick, tribal chairman of the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation, speaks at a news conference at the Illinois Capitol in February 2024. (Peter Hancock / Capitol News Illinois)

A Native tribe has received back a portion of its ancestral land in Illinois, marking the first federally recognized tribal land in the state.

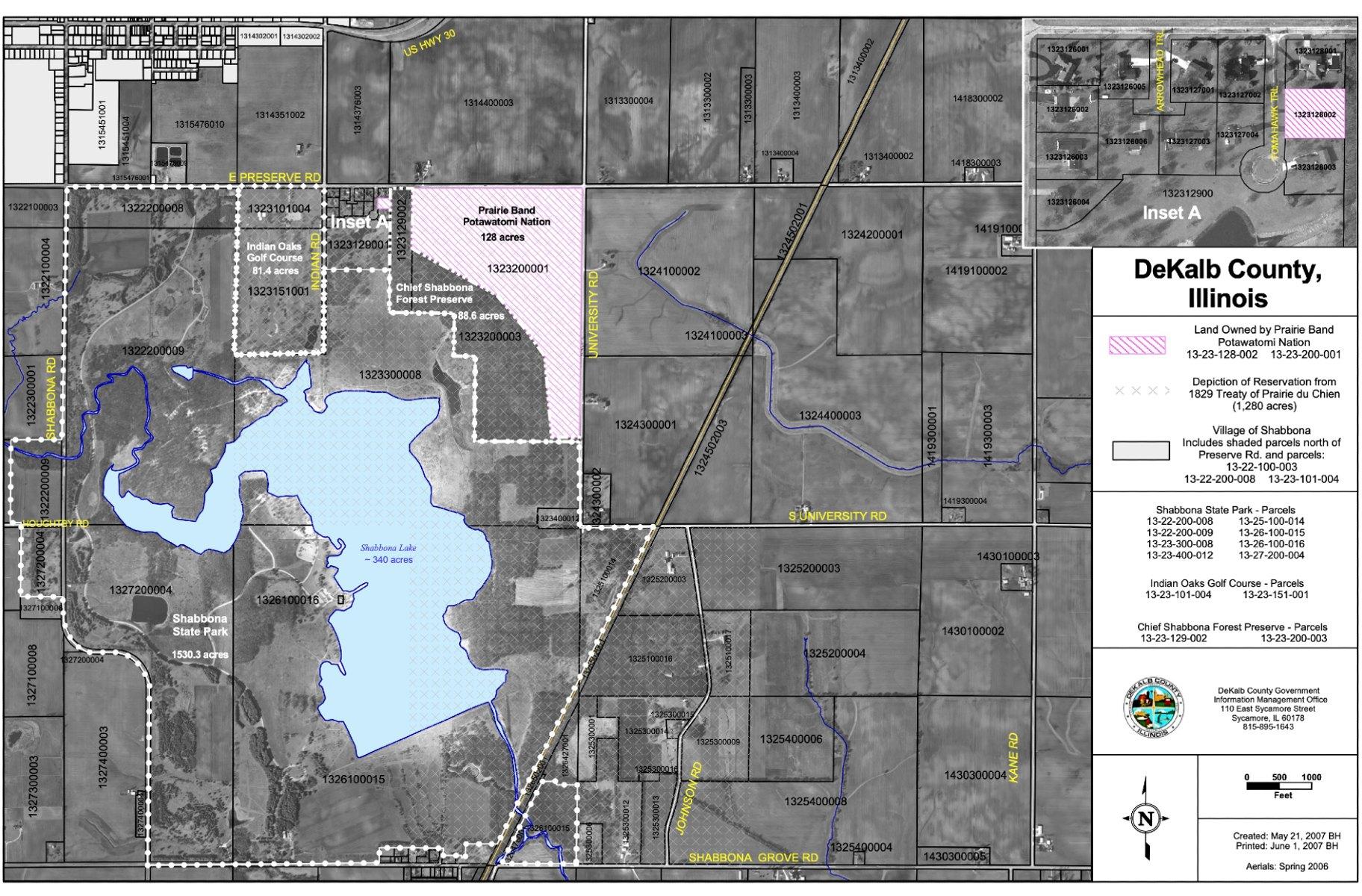

The decision announced Friday by the U.S. Department of the Interior places portions of Shab-eh-nay Reservation land, which is located in DeKalb County, into trust for the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation, which gives the tribal nation sovereignty over the land.

The decision comes 175 years after the U.S. government illegally auctioned off 1,280 acres of land in northern Illinois owned by Prairie Band Potawatomi, according to the tribal nation.

The Shab-eh-nay Reservation land includes portions of Shabbona Lake State Park in DeKalb County, named after Chief Shab-eh-nay of Prairie Band Potawatomi.

A map of the 130 acres of land the Prairie Band purchased in DeKalb County that now makes up the tribe’s federally recognized reservation. (Provided)

A map of the 130 acres of land the Prairie Band purchased in DeKalb County that now makes up the tribe’s federally recognized reservation. (Provided)

“We have been asking for this recognition and for what is rightfully ours for nearly 200 years, and we are grateful to the U.S. Department of Interior for this significant step in the pursuit of justice for our people and ancestors,” said Prairie Band Chairman Joseph Rupnick, the fourth generation great grandson of Chief Shab-eh-nay, in a news release.

The Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation said it will “carefully evaluate” potential uses for the land, but no immediate changes for usage have been decided.

All current homeowners will continue to retain title to their land and will live in their homes undisturbed, the tribal nation added.

The Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation originated in the Great Lakes region but was forcibly removed in the 19th century. The tribe is now headquartered in Kansas.

Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation Chairman Joseph “Zeke” Rupnick poses with members of the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation. (Provided)

Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation Chairman Joseph “Zeke” Rupnick poses with members of the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation. (Provided)

A History of the Shab-eh-nay Land

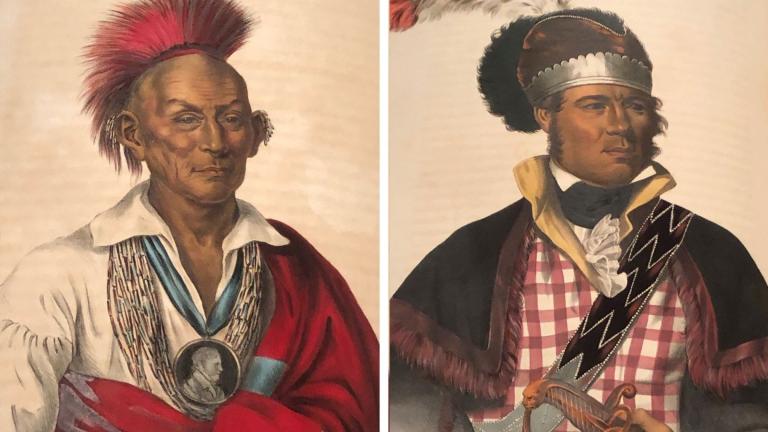

As Rupnick told the history to Capitol News Illinois, the land that now makes up Shabbona Lake State Park was set aside for Chief Shab-eh-nay and his descendants in 1829 as part of the Treaty of Prairie du Chien.

The following year, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, which gave the president authority to grant land west of the Mississippi to Native Americans in exchange for giving up their tribal lands in the east.

In 1833, the Potawatomi signed the Treaty of Chicago in which they ceded nearly all their land along the western shore of Lake Michigan – all except the roughly two square miles reserved for them by the Treaty of Prairie du Chien.

From there, the Prairie Band Potawatomi splintered, with some moving to Canada and others moving west to Missouri and Kansas. In the 1840s, with money they received for ceding their land in Illinois, the Potawatomi bought a 30-by-30-mile reservation in Kansas, about 30 miles north of what is now Topeka.

But Chief Shab-eh-nay and about 20 to 30 other members of his extended family stayed behind on their land in Illinois. That is, until about 1850, when Shab-eh-nay took a trip west to check in with the rest of the tribe in Kansas to make sure they were settling in.

“Of course, you couldn't make that drive like you can in eight hours today,” Rupnick said in an interview with Capitol News Illinois.

Traveling by horseback or wagon, Rupnick said, Shab-eh-nay was gone from Illinois for several weeks.

“Once he got back here (to Illinois), that's when he discovered that people were living in his house,” Rupnick said. “They actually picked up his house and moved it to another location, and people were living in it. He tried to fight that through the court systems. They told him that he had abandoned his land, that the General Land Office had sold all of his land because he abandoned it. And they allowed the settlers and whoever else to live there.”

Capitol News Illinois reporter Peter Hancock contributed to this report.

Contact Eunice Alpasan: @eunicealpasan | 773-509-5362 | [email protected]