Chicago’s brick buildings put on a refined face for the street side, but if you peek past the facade, you’ll find that what’s holding them up is a little bit rougher.

Geoffrey Baer tells us about the not-so-common brick that built Chicago.

My wife and I are fans of the HGTV show “Hometown” which focuses on a couple updating and remodeling homes in Laurel, Mississippi. They refer to “Chicago brick” in many episodes of the show. What is “Chicago brick” and what is its origin and history?

— Lloyd Fry, Chicago

If you’re like many Chicagoans who live in a brick home, chances are good that your home is built mostly of, well, Chicago brick — which is to say, the Chicago common brick. This native son of our city is the Grabowski of building materials – rough around the edges and full of character, imperfections and diversity, much like the city itself.

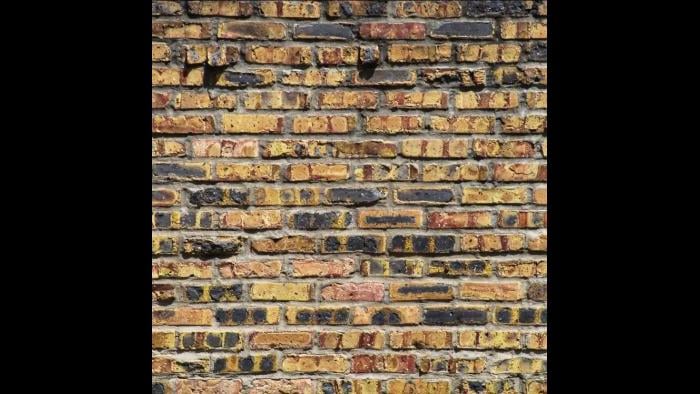

That’s because of the clay beneath our feet here. It was deposited around the shore of Lake Michigan and well inland by the last glaciers, which receded about 10,000 years ago. It’s called blue clay and it’s fairly close to the surface so it’s easy to mine. Blue clay is high in lime and iron and it’s littered with pebbles and other glacial debris, so when the bricks are fired in a kiln they turn a variety of colors, from dusky yellow to pale pink, and they are speckled with all the bits and piece that were embedded in the clay.

By comparison, the clay under St. Louis is much smoother and high in iron oxide so it turns a beautiful, uniform red when fired in a kiln. Milwaukee’s famously cream-colored bricks – that’s right, it was bricks, not dairy, that gave Milwaukee its nickname “Cream City” – are made from a red clay containing high amounts of lime and sulfur.

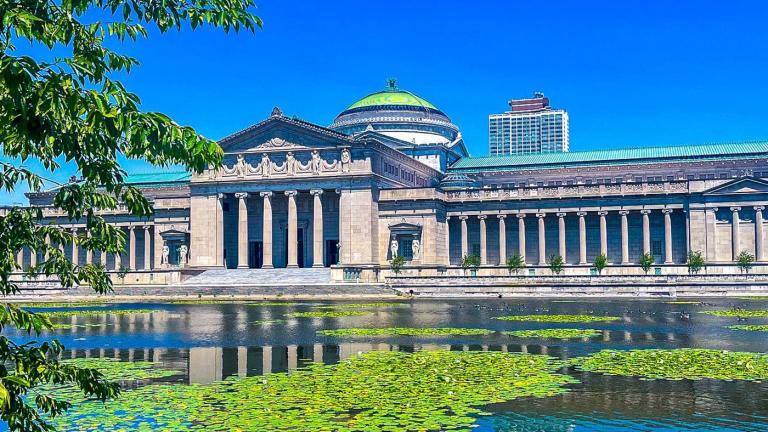

Back in Chicago, the city’s status as a railroad hub in its formative years meant that it was a crossroads for all kinds of brick, so we’re fortunate to have a wild, wide diversity in the brick that makes up the facades of our buildings.

But all you have to do is peek behind the face to find the Chicago common brick used on the sides and rear facades and internally for foundations, chimney flues and structural walls. That’s because it was much cheaper and easily available, which made it attractive to builders far beyond Chicago.

Chicago brick cost about $5 to $10 per thousand bricks, compared to as much as $35 per thousand for face brick, according to Chicago’s foremost brick expert, Will Quam, who operates the website Brick of Chicago and gives brick tours and was our key to answering this question. You might remember we featured him on “Chicago Tonight” last year, when he showed us St. Stanislaus Kostka Church from 1881 in Pulaski Park, which was built entirely of Chicago common brick, even on the façade, to save on construction costs.

(Courtesy Will Quam)

(Courtesy Will Quam)

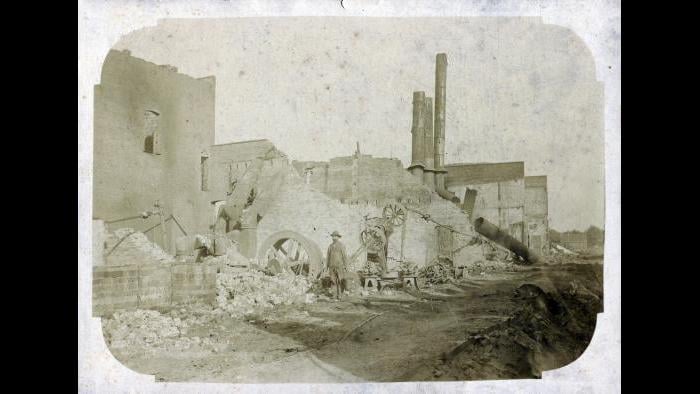

Chicago’s brickmaking industry boomed after the Chicago Fire of 1871 when new building codes made it all but impossible to build with wood.

In 1910 the city produced nearly a billion of these “humble cubes of clay” as one writer lovingly described them that year. At one time there were clay pits and brickyards all over Chicago and in suburbs like Blue Island and Park Ridge, which was originally called Brickton. The community dropped the name in 1873 after the clay was all mined out.

The last Chicago common brickyard closed in 1981, and most of the brickyards that once dotted the city were filled in and built over (both Horner Park and Lane Tech High School were built on the sites of former brickyards). But one had a brief run as a ski resort. Thunder Mountain in the Montclare neighborhood opened in 1968 to take advantage of the 285-foot pit created by digging clay for bricks. The family that owned the Carey Brick Company used the pit to ski on occasion, and after the famous blizzard of 1967, decided to give it a shot as a business. Sadly, the only ski resort Chicagoans could travel to via CTA bus closed just two years later after two disappointing winter snowfalls. Later, the site would become a shopping center named – you guessed it – the Brickyard.

By the time shopping malls were in vogue, Chicago brick manufacturing had become a thing of the past. Newer building techniques including steel and concrete block are cheaper for structural applications, and bricklaying is very labor intensive. Old brickmaking operations couldn’t comply with modern environmental laws without costly modifications, and perhaps most importantly, all of that blue clay that was cheap and easy to mine was exhausted.

But in recent years, reclaimed common brick has surged in popularity in Chicago and as far away as Mississippi if that HGTV show is to be believed. When old buildings are torn down in Chicago, the bricks are salvaged, cleaned and resold, and not just to play backup for pretty face bricks. Finally, Chicago common bricks are having their moment of fashion!

These days, people have come to prize the old bricks for their character, having weathered and mellowed on buildings for decades or even more than a century. Loft conversions expose the brick in existing buildings, and reclaimed brick is often used in new construction.

So next time you’re walking through your neighborhood, spare a fond thought for the uncommonly common Chicago brick – the brick made of Chicago, for Chicago.

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city’s past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city’s past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Do you have a question for Geoffrey? Ask him.