Marc Schlossman, pictured with bird specimens at the Field Museum, Oct. 25, 2022. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Marc Schlossman, pictured with bird specimens at the Field Museum, Oct. 25, 2022. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

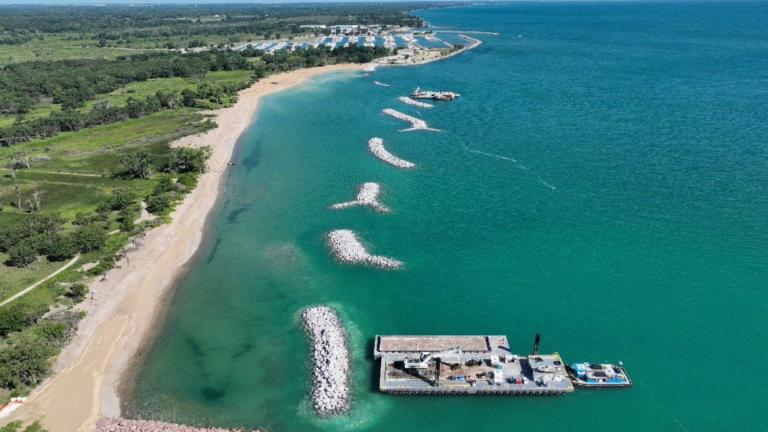

During a backstage tour of the Field Museum’s specimen collection some 15 years ago, photographer Marc Schlossman had a moment of clarity.

The ivory-billed woodpecker he held in his hand — a species last seen in 1944 — could be found nowhere else in the world, outside of such assemblages.

It was a thought that inspired both awe and anger. “Enough is enough,” he thought. “We’ve got to do more to be better stewards.”

That moment marked the beginning of what would become a decade-long odyssey to photograph specimens of other extinct and endangered species housed at the Field, exhuming them from drawers, cabinets and jars, and instilling them with new life.

The project initially had no specific aim, gradually morphed into a blog and eventually jelled into a book, “Extinction,” published in September.

Despite the title, Schlossman said the book isn’t a lament but rather an “exercise in hope.”

Of the 82 species featured in the book, only 23 are actually extinct. The remainder are either on the knife’s edge of disappearance or are conservation success stories, like the California condor, brought back from the brink.

“Eco-anxiety is a real thing, we do get stuck on negative messages. But there’s a lot of positive out there. I wouldn’t do [the book] if I thought we were out of time,” Schlossman said. “This book is about, ‘Let’s save these things we have left.’”

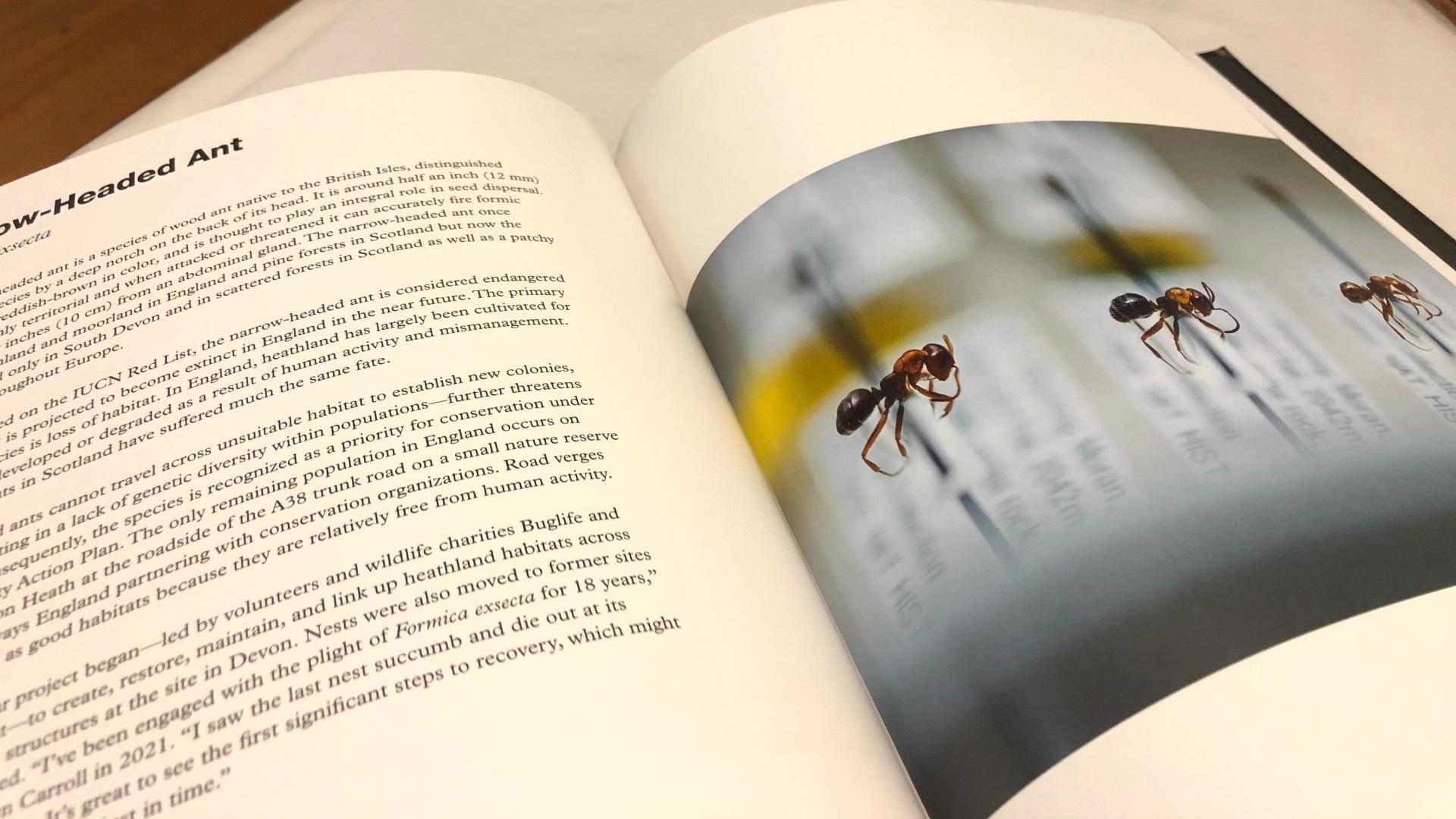

The narrow-headed ant is among the endangered species featured in "Extinction." The book's goal is to raise awareness and spur conservation efforts. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The narrow-headed ant is among the endangered species featured in "Extinction." The book's goal is to raise awareness and spur conservation efforts. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Of the Field’s holdings, only 1% are on public display. The other 99%, like the ivory-billed woodpecker, are kept in storage, a biological record of earth’s biodiversity that serves as a resource for researchers around the world, including, in the case of “Extinction,” a curious photographer.

“There’s so much more here than dinosaurs and mummies,” said John Bates, curator of birds at the Field and author of the book’s foreword. Specimens, he said, are often used to fill in historical data gaps in long-term monitoring studies, where gathering information in the field is no longer feasible.

To get a sense of the vastness of the museum’s collection, consider this: During high school, Schlossman, now 61, volunteered at the Field and spent an entire summer labeling nothing but mink specimens.

The experience hinted at the immensity of the planet’s inhabitants and inspired Schlossman to study wildlife biology in college. He could well have wound up back at the Field as a staff member if he hadn’t picked up a camera and fallen in love with photography. With “Extinction,” Schlossman found a way to marry both passions.

The project proceeded in fits and starts, with Schlossman, based in London for the past 35 years, traveling to Chicago for a week or so at a time, two or three times a year. Bates helped open doors at the Field for Schlossman, who ultimately gained access to collections ranging from invertebrates to insects, mammals to botany. That last category, he said, is often ignored in discussions about extinction.

“Lichens, liverworts, ferns — who cares about them?” he said. “I wanted this book to address that.”

In advance of every visit to the Field, Schlossman would research potential subjects, aiming for a balance between well-known species — such as the passenger pigeon, once numerous enough to block out the sun and famously wiped out in just 30 years — and more obscure specimens.

He was looking for interesting stories and found them in species like the Albany cycad, a tree so prized for its rarity, thieves poached a cluster from a botanical garden in South Africa; or the Columbia River tiger beetle, whose dwindling numbers have made it attractive to collectors, compounding the threat to its continued existence.

As he set up his occasional makeshift photo studio among the specimen stacks at the Field, Schlossman found he had to build time into his workday for chats with staff.

“People would walk by and say, ‘Wow, what are you doing? That's cool,’” he said. Often the conversation would lead to suggestions from researchers of other species he might want to consider photographing and on occasion, Schlossman said, he’d return to the Field in the morning to find new specimens on a cart.

“That’s one thing I never expected, that people who work here would become collaborators,” said Schlossman. “I learned so much.”

The challenge for Schlossman as a photographer was to find a way to reanimate and lend personality to creatures and organisms that were now inanimate objects. Apart from butterflies and insects, many had lost whatever color they once possessed, leaving him with a predominately gray and brown color palette. “Wet specimens,” preserved in liquid in jars, were difficult to shoot due to reflection from the glass.

His solution often was to train focus on a single detail, zooming in on the claw of a sunda pangolin or the mouth of a grey wolf skull. “In some cases, I wanted them to look like evidence shots,” Schlossman said, implicating humans in the crimes of pollution, overexploitation, climate change, hunting and habitat loss.

Each specimen image covers an entire page in “Extinction,” placed opposite a “biography” of the pictured species, as well as its range and conservation status, contributed by Schlossman’s collaborator, Lauren Heinz.

“The best thing this book can do is raise awareness and bring people closer to the stories, closer to nature. The scientists here, they all say, ‘Let’s work harder to conserve what we have,’” Schlossman said. “We’re not going to get back to an original state but on a continuum of the Garden of Eden to doomsday, there has to be someplace in between.”

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]